“Never try to convey your idea to the audience – it is a thankless and senseless task. Show them life, and they’ll find within themselves the means to assess and appreciate it.” Andrei Tarkovsky

And so, most fittingly, Father James’ life is measured not so much by the obviousness (or lack) of his own virtues, but by his ability to teach others to recognize and embrace the superhuman path to virtue that lies before them; a path that he fights to walk each and every day, even as they do.

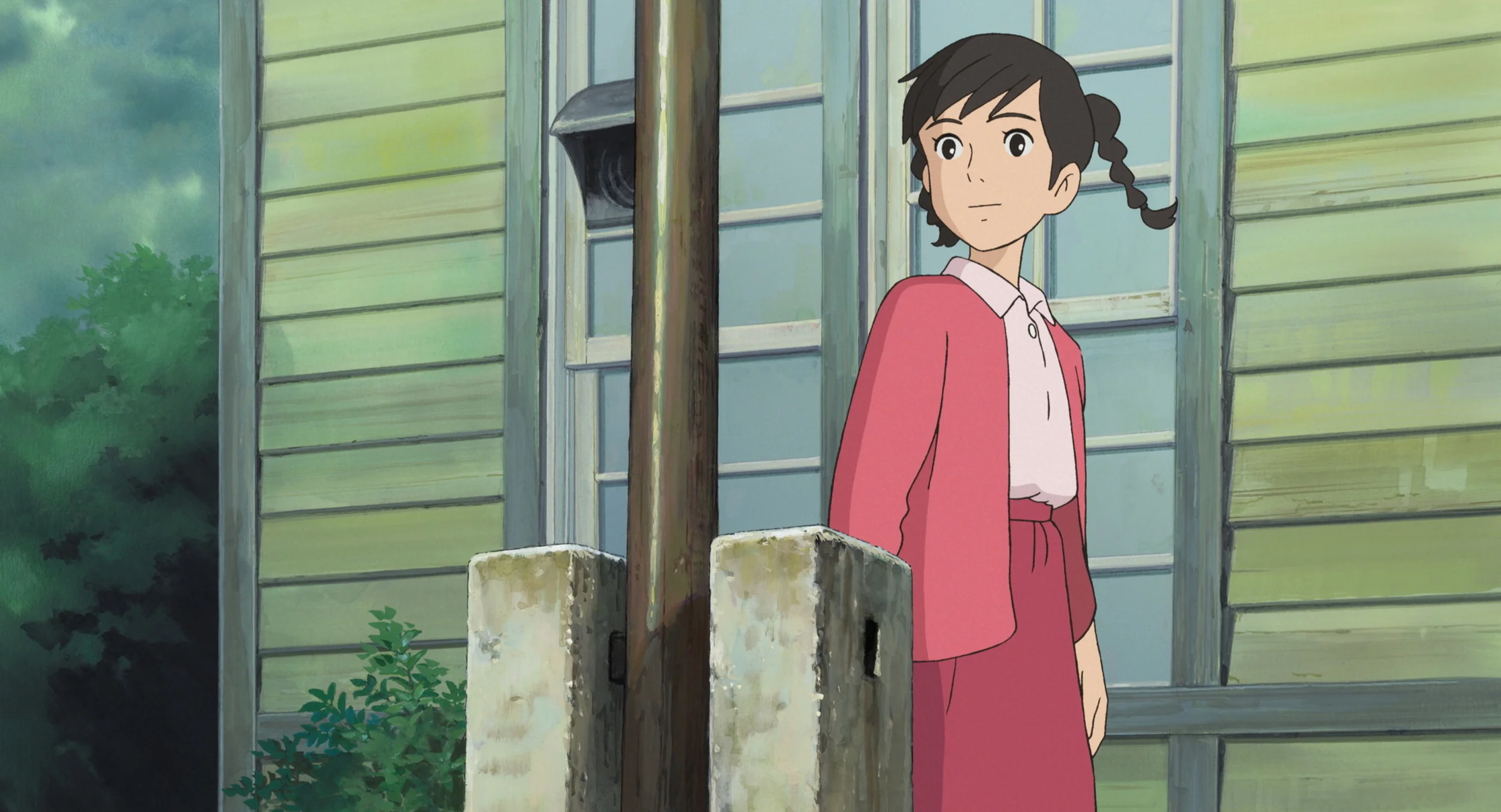

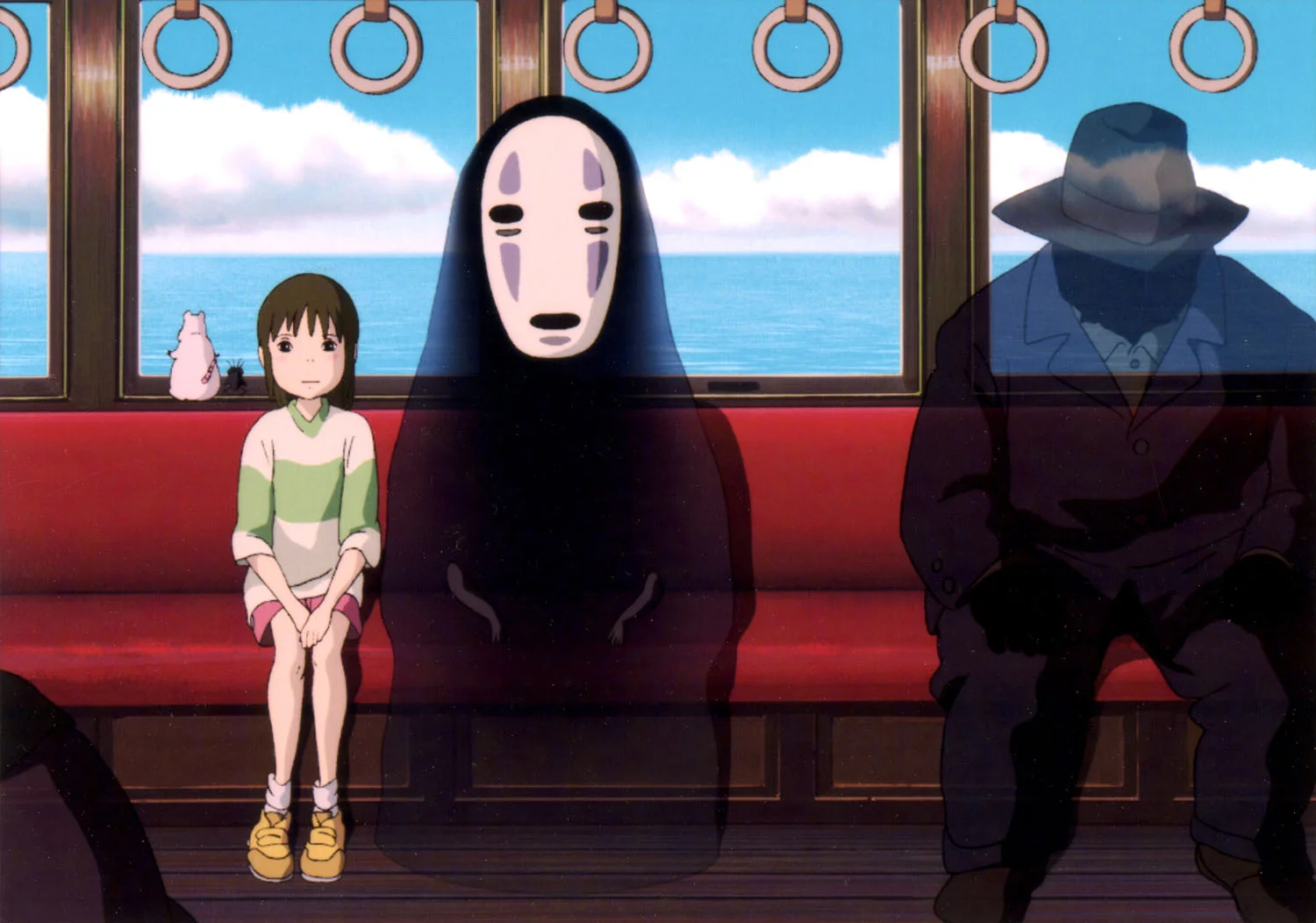

I suspect that Goyo [Miyazaki] has discovered that the best way to follow in his father’s footsteps is to recognize and embrace his philosophy — “Give room to the reality of the heart, of the mind, and of the imagination” — but to paint that reality upon an entirely different canvas.

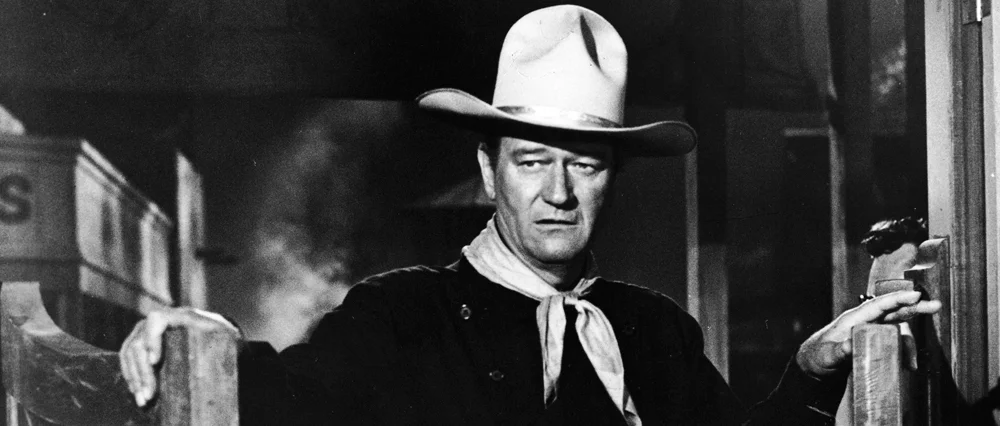

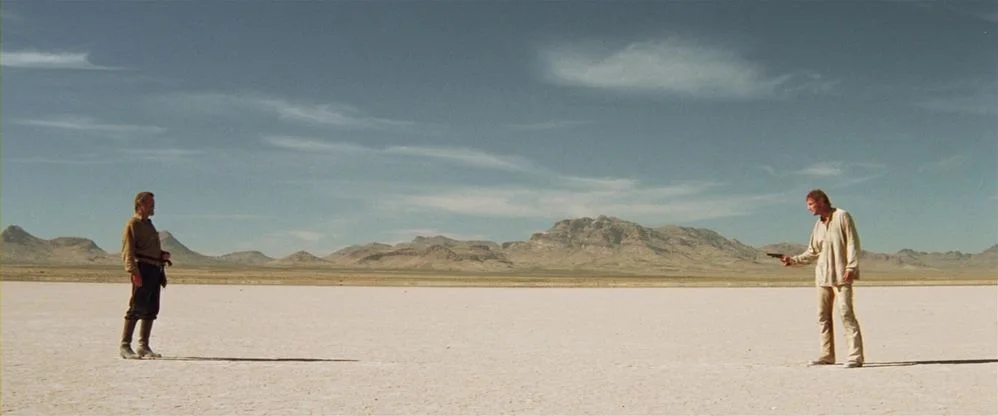

Tellingly, it is not Doniphon's revelation of the truth behind Valance's death that proves most compelling, but his reminder that Stoddard has forever altered the life and expectations of the film's heroine, Hallie (Vera Miles), and that there are certain obligations he must embrace as a result

Above all, this is "a classic tale of good, evil, and moral courage," and Jackson's meddling does not abolish that fact -- but it does make it significantly harder to recognize. The louder and larger the spectacle, the less obvious (and less important) Bilbo's modest heroism becomes.

We humans excel at convincing ourselves that intrinsically evil actions are either not truly evil or somehow do not apply to us. But only slightly less destructive is the ability to assure ourselves that "smallish" evil is acceptable if committed for the sake of some "larger" good. To build upon the paraphrased wisdom of Keyser Söze, while the Devil's greatest trick may be to persuade us that he does not exist, his greatest subversion is to convince us that he just wants to help.

Fear, failure, suffering, and sin are inescapable components of our fallen human condition, and while we can resist them in this life, they will never be eliminated from "this vale of tears." Heroism and the confrontation of evil—a confrontation most often achieved through suffering—is the only way to truly grapple with the problem. To paraphrase Alfred, we must learn to get back up; to rise again, and press ever forward towards the light.

Essentially, the good doctor is a character witness. While sometimes bemused at his unshakable faith, we have no doubt about the veracity of his insights. Our trust of this simple, kind-hearted man and our confidence in his judgment runs far deeper than our distaste for Holmes and his ego-centric tendencies.

Questions of honesty, intent, and the danger (or value) of lying—questions that have produced much consternation and controversy (and genuinely helpful conversation) in the Catholic blogosphere—drive the film's most obvious moral problems. But beneath those questions lies one that has long been lurking on the outskirts of my conscience: Why does the Psalmist's warning concerning idols and their makers center around the chilling reminder that "They that make them are like unto them?"

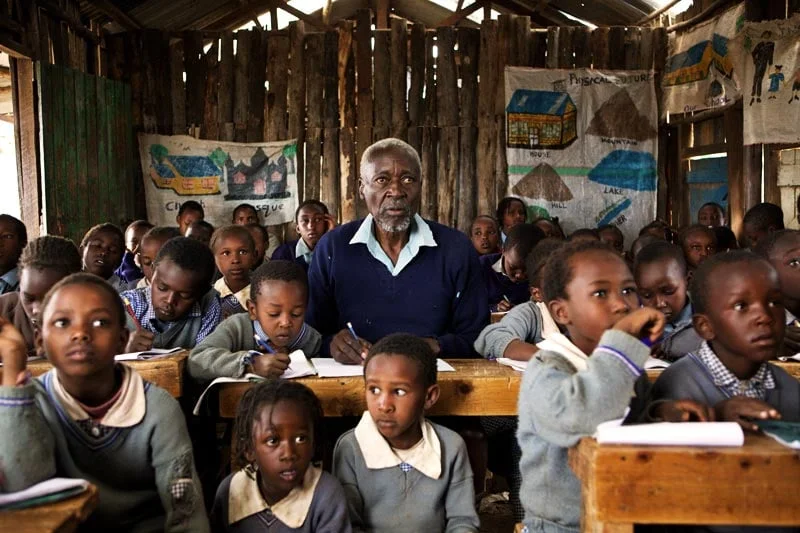

The importance of education; the way our drive for freedom impacts everything we do; the power of perseverance—all are explored by the film in timely (if not always profound) ways. But the most intriguing insight offered is a reminder of how important it is to be grateful to our political and cultural forefathers, and how vital it is to recognize both their extraordinary accomplishments and their inevitable mistakes. Few things will guide our futures as well or as clearly as remembering those who came before us, and upon whose shoulders we stand.

There is a grave danger in seeing ourselves as the final arbiters of another's happiness, worrying that an obstacle they face may prevent them from living an "ordinary" life while failing to recognize the extraordinary gift their presence is to so many.

How easily we lose sight of why exactly God is giving us something, overemphasizing the things we desire the most in that which He grants us, ignoring what is most valuable for the sake of lesser goods, and missing the point of His generosity altogether. We humans are not just in the business of looking gift horses in the mouth; we want to turn them into unicorns.

Mary and Martha, so often relegated to opposite sides of the spiritual spectrum, would doubtless recognize that I am not focused on my kids instead of God; I'm focused on them because of Him. And that praying through the distractions of my family does not render my devotions powerless, but imbues them with more power than I could ever have achieved on my own. Was it not He Himself that commanded us to let these little distractions come to Him?

Yet He takes us back to Him even after the brutal betrayal of the Cross, and He has done it every moment of every day since that afternoon on Calvary. God does not do it because He needs to "move beyond" the Cross; He does it for no other reason than our own salvation. He has nothing to gain, and we have everything. How absurd and all-consuming is God's forgiveness; how impossibly unlike human forgiveness.

None of us would knowingly place ourselves in a position as extreme as Lear's, embracing or banishing one's family on the strength (or weakness) of their fawning. Yet in a subtle way, we are all susceptible to Lear's fatal weakness, often giving more weight to the opinions and suggestions of those who praise us than to those whose words are designed to help us grow, but may sting a bit, as well. Demanding protestations of love as a prerequisite for acceptance, and measuring out the size of our rewards in conjunction with their avowals is far more common than we would care to admit, and who among us can honestly say that we bear criticism as well as we relish praise?

There is an undeniable absurdity to creating giants where there are none, yet it is just as common to reduce the very real giants before us to mere windmills for the sake of political expediency (and to assuage the pricking of our consciences for those battles we have already lost).

Like the lamb of Isaiah, little, long-suffering Balthazar does nothing to merit the cruelty he experiences. The silent patience with which the tiny donkey embraces all that befalls him is rendered more extraordinary because we recognize how undeserving he is of such suffering. By contrast, a human being—even the tragic Marie—can never be seen as completely innocent. She, like all fallen humans, carries within herself the seeds of her own destruction, and while we grieve at her lost innocence, it is impossible to consider her a "spotless victim."

Just as Pieter's singleness of vision wore down the boundaries between the world in which he lived and that he sought to portray, so too we—by diligent adherence to our Lenten observances—will narrow the gap between the person we are and that which we wish to be. Eventually, the rediscovery of our Lenten selves will cease to be an annual exercise in frustration, becoming instead a reflection of our true selves.

I remember those days of young love well, and cherished every moment of them. Yet, six sons into the adventure, I find such fare a great deal less appealing—not because they deal with something untrue or even unimportant—but because they deal with it on such a superficial level; it's the stuff of beginners.

Despite the insistent clamoring of Modernity, happiness is not something to be grasped at; paradoxically, the more we pursue it, the less of it we actually have. A failure to recognize our own powerlessness will leave many more sorrowful than they were when they first began this pursuit, for we humans will never succeed in "capturing" the peace and contentment we so ardently desire.

Obsessed with the "beautiful" nostalgia of the past, Cassidy has made a frightfully common mistake: he has assumed that ordinary, everyday life isn't romantic, when the truth of the matter is subtly (but vitally) different. It's not that ordinary life isn't romantic; it's that it isn't romanticized. Cassidy has mistaken flashy appearances for the truly worthwhile struggles of everyday life, and his inability to embrace ordinary challenges of living will prevent him from ever achieving the folk hero status he so desperately desires.

The Naked City reminds us that instinct to hide behind such facades is a powerful one. Faced with the challenges of daily life, many of us create personas to cope with those things we find most challenging—easily defendable fortresses that hold the harsher, more demanding "realities" of our world at bay. Sometimes, these masks are a means of escaping (and hiding) from the truth. But sometimes, they are a sign of progress rather than a sign of escape. Sometimes, these masks are created to protect those we love rather than to hold them at arm's length.

As the current presidential primary makes abundantly clear, having a handful of funny, simple, and (above all) short answers is far more important than having a nuanced, thoughtful grasp on complex issues. Our generation unconsciously bestows the veneer of entertainment upon anything it sees on TV, transforming themselves from constituents looking to be won over, into nothing more than "audience members." And audiences aren't looking for complex answers; they're looking for amusement.

...even God does not consider us independent of our human relationships, but in our totality within them. I am not only "Joseph," I am also "Dominic's father." And that paternal relationship profoundly influences us both. At the Final Judgment, I will be called to answer not only for my own life, but for the impact I have had on the lives of my children.

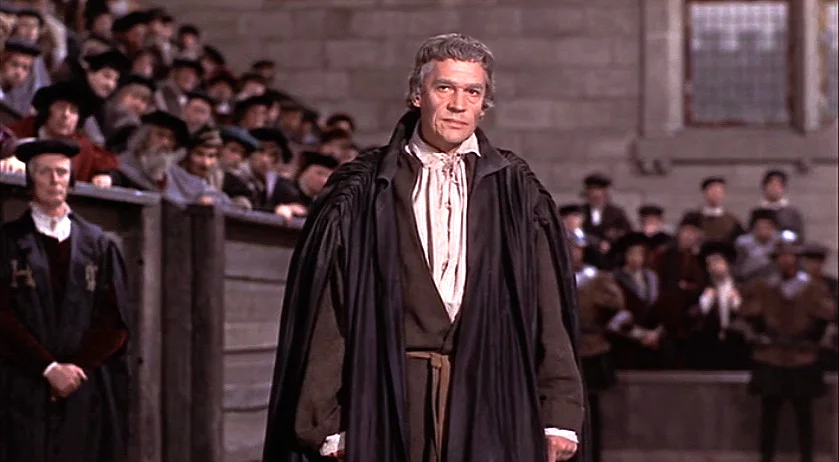

For More, sharp of tongue and even sharper of intellect, this moment is an opportunity to reach out one last time in an attempt to show his weak young friend the truly damnable blunder he has made. But for the audience, it is that most cathartic of moments when Rich's betrayal is shown in its true light, the absurdity of fatally compromising one's soul for something as transient and fleeting as worldly fame and fortune, cast into sharp contrast with More's impending martyrdom.

Fairy tales are not unrealistic; they're supra-realistic, underscoring the absurdly wonderful, fantastical world in which we find ourselves, and reminding us of the One who placed us in it. There are dragons, yes, but there is Someone to subdue them, as well. And if we have the one, resplendent in all its fairytale-encrusted glory, must we not also have the Other?

Self-improvement is a good thing, and we could all do with a bit more of it. Too often, though, we find ourselves obsessing over how we are perceived, working overtime for the approbation of people who don't know us well, yet whose approval we paradoxically value above all else.

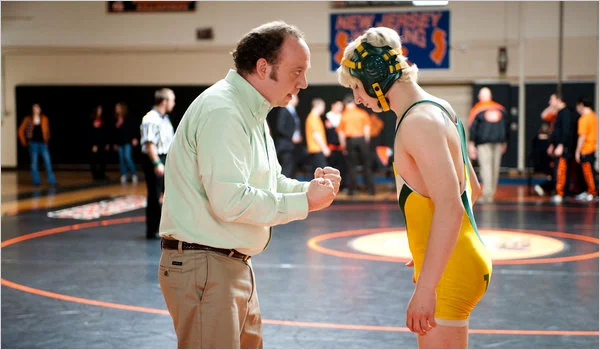

Despite the encouragement of Charlie Sheen and Al Davis, winning is far less important than being right. Our stubbornness and our pride in the validity of our positions can be a valuable tool. But we must never allow that stubbornness—our own deep-seated desire for victory—to get in the way of what is true.

How can God forgive someone who does not recognize their own need for forgiveness? Sure, a "debt" could be paid, but what would that payment mean if there was no spiritual transformation to accompany it? We must be transformed if we are to be perfected, yet there is no transformation without recognition and acceptance of our own personal, insurmountable failings.

To truly embrace our roles as stewards, we must learn to listen as well as to command. The subjugation of Nature will only succeed if we recognize the importance of the stewardship to which we have been called. It is easy to assert our importance in the order of Creation, but Heaven help us if we refuse to recognize that safeguarding the integrity of this harmonious universe is as vital a part of our human nature as is our dominion over it.

Indulging our natural curiosity is only an impediment to action when we fail to recognize the humanity of those we are observing, mistakenly viewing them as things rather than people. Mistaking "watching" for "acting" is only possible when we, like Folke's fellow HFIers, "maintain a safe and sterile emotional distance." But dissolve that distance, and our innate desire to interact with our fellow human beings will return in full force.

In those panicked moments, the fear can be overwhelming; the desire to withdraw into the safety of one's self is an easy solution to the exhaustive obligation of parenting. That instinctive shrinking from responsibility, understandable though it may be, ignores both the good we parents do without realizing it and the grace God gives to us as parents. We have been given to power to serve as the most immediate, most formative forces for good in the lives of our children. But we can't be that force without simply being there in the first place.

Teaching by example is an important part of living out our lives as effective parents and faithful Catholics. But it is vital to remember that while "actions speak louder than words," they don't always say exactly what we want them to say, even to those nearest and dearest to us. Sometimes, what we do is less vital to our children's formation than why we did it.

The emptiness of the New York skyline is an emphatic reminder of the extraordinary heroism, nobility, and self-sacrifice that rose from the ashes on that day—a heroism that represents New York just as surely to our generation as those two great buildings did in the decades before September 11, 2001. And as long as we can see these vacant spaces and remember our heroes, we will not be defeated or disheartened by those seeking our abolishment; we will have won.

It would be a shame to dismiss his gentler work as nothing but childish amusement. Like the Pixar films he has influenced, Miyazaki’s creations are both entertaining and enlightening; for him, animation is the lens through which he looks at life, not a way to distance himself or his audience from its lessons.

The boys respond to this apathy with false bravado. But the actions of these wayward children are clearly shown for what they are: hollow attempts to defend their fragile emotions and frailer psyches. Giuseppe, Pasquale, and their fellow cellmates are most definitely children; their swaggering, calloused behavior merely an effort to hide their childhood before someone destroys it.

The film, by delving into the story behind Max's behavior and those of his huge, furry friends, eliminates much of the mischievous charm of its source material; the childlike exuberance which permeates the picture book is largely absent in Jonze's work because the audience knows too much about Max and his Things. Where the Wild Things Are is inappropriate for children because it's sad, not because it's scary—sad about things and emotions which they cannot possibly begin to understand.

Our need to wrestle meaning from such Evil, often leads us to blame cultural, political, or religious ideologies, but this kneejerking blame-game is not only politically and spiritually unhelpful, it is misguided. Even the most clearly-stated of intentions will never fully explain such depravity; ideologies and motivations will never truly match up to the unthinkable actions conceived and carried out by misguided fanatics.

How often are we willing to compromise on smaller matters, setting aside what we know to be right and just for the sake of our own desires? Surely, we would not kill another to further our own ends, but how many of us are willing to ridicule and belittle others in the feverish building up of our own importance? Are those two groups really so far apart? How far will we go to get what we want?

Though the story is Elmer's, Sister Sharon Falconer has a vital lesson to teach. Once overlooked as an earnest, inexperienced supporting player in Gantry's dramatic story of self-discovery, she becomes the all-important "flip-side" of the story - the effect that adulation can have upon the one being followed. This devout and well-intentioned young woman begins to view herself as more than a simple human instrument. Her followers have come to rely so completely on her spiritual strength that she now sees herself as The Only Instrument by which they can be saved, and her inability to reject her new-found fame for an "ordinary" life will have tragic and lasting consequences.

In one of the season's most powerful moments, a young woman known as Fleur Morgan chastises Tate for his willingness to experiment on a baby clone recently captured from its parents. "It's a baby," she says. "I don't care if it's a baby human, a baby AC, or a baby chimp. It wasn't born for our benefit."

The notion of jealous and dissatisfied angels seeking to emancipate themselves from a desire-less world by becoming human is ludicrous. Yet there is a lesson here to be learned about the importance of desire, and about how interwoven and fundamental desire is to our human nature. If Wenders' angels wish so desperately for desire, perhaps we should not cast it off so lightly.

Yet despite the darkness of its "evening," the film never loses sight of its "sun." Grudging admiration comes gradually both for Choat (whose stubborn resolve to better himself for the sake of his family is undeniably praiseworthy) and Abner (whose eventual acceptance of his old age and deteriorating health is matched only by the painful, redeeming recognition of his own failings).

Muniz's own journey is deeply uplifting. In the film's opening moments, he expresses concern for his safety amidst the catadores. But by its conclusion, he is overwhelmed by the goodness and decency he has found among them. They are not redeemed by his art; rather, his art has been transformed by the extraordinary beauty and honesty of their lives—lives lived out cheerfully in the midst of great poverty and suffering.

When horror icon Wes Craven chose it as the inspiration for his exploitation film The Last House on the Left, he seemed to put an exclamation point to that misconception, which misses the film's central point entirely; at its core, The Virgin Spring speaks of the diametric opposite of horror and revenge: resignation.

Hulot (and Tatischeff after him) is often childish rather than childlike; his simplicity a façade that masks an unbecoming reluctance to interact with others. Recognizing the dangers of modern technology is one thing; asking how one can best overcome those dangers is something else altogether. Tati never allowed his Hulot to confront that question, but Chomet does.

Like all created things, we exist in the "Here and Now"—a tiny jetty of stability jutting out into the roiling surf of the Past and the Future. But unlike our less rational Earth-dwelling companions, we humans are uniquely capable of manipulating that vast chronological ocean, using our memories as life-saving reference points and our dreams as vital motivations for our present actions.

More Jerome than Thérèse, Monsieur Vincent's tireless exertions on behalf of his beloved poor are threatened by the sharpness of his tongue for those he sees as obstacles to his important work. When his faithful followers balk at the added burden of caring for Paris' orphaned infants, Monsieur Vincent lashes out, decrying their unwillingness to give above and beyond what they have already given.

In many ways, childhood is the most defenseless of human stages. Yet in His wisdom, God has given children an extraordinarily irrepressible nature, and their ability to weather such storms as war and the loss of those most vital to one's growth, scathed yet unbowed, has been essential to our very survival.

Faithfulness to Christ and His Church will never be easy. We are all tempted to betray Him in a thousand little ways, each and every day. But with such an extraordinary example of Divine Madness and Mercy lifted up before us, how could we not follow in His footsteps, even though they lead us to the Cross? For despite the fear and pain of the many little crucifixions to which He calls us, we must remember that Good Friday is only a step along the path that leads to Easter.

...such powerful emotions cannot undo the fact that each individual member of the human race is implicated in the brutal events at Calvary. Even as we recoil from the injustice of His death, we recognize that we have placed Him there through our own selfishness and pride.

Despite the unrealistic depictions of volcanic, all-consuming love that permeate our culture, few of us are called to love on a spectacular, melodramatic scale. In fact, many of us will show the greatness of our love not through the depth and power of our romanticism, but through the toils and joys of ordinary life.

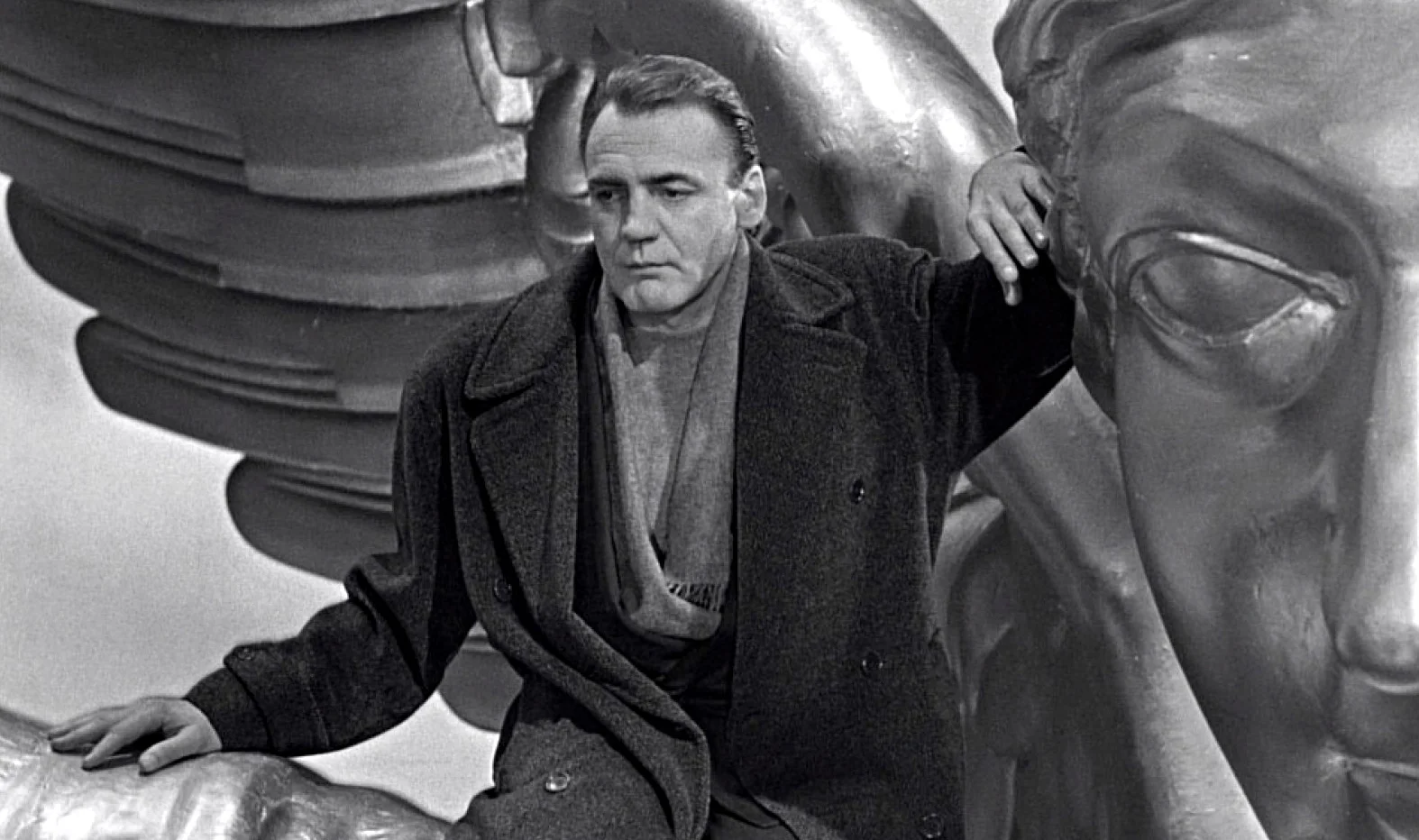

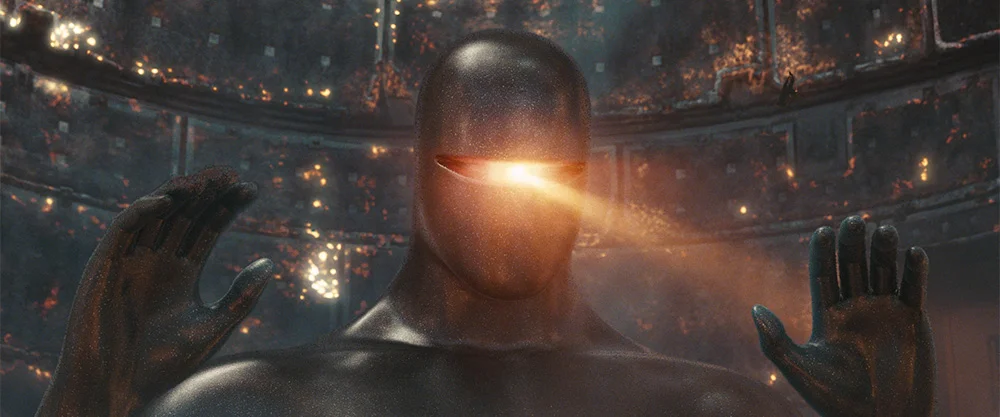

The new Klaatu is no prophet crying out for repentance; he is an avenging angel sent to mete out harsh justice on a race gone hopelessly astray. Yet he is also an angel transformed by his experiences and by the undeniable beauty and self-sacrifice he has seen on Earth.

Blessedly, few of us will ever be called to confront remorse as grave as that which plagues Juliette. And yet, no matter how grievous our guilt may be, we have a far greater Friend than Léa to guide us through our repentance. Like Léa, God is uncompromising in His love; like hers, it is freely given and immeasurable, "pressed down, shaken together, running over."

Our hero is defeated not by Labor or by Capital; he is defeated by the profoundly human tendency toward inertia. A life spent slaving away in a textile factory might not seem like much of a life, but at least it doesn’t require one to make difficult decisions, or strike out into an unknown and challenging new world.

That's the wonderful thing about the Body of Christ: We are not alone. True, "when one falls, we all fall," and goodness knows there's enough falling to go around. But the bearers of Grace are everywhere, as well. We bear it to each other, often without even knowing it.

The happiness of the Marquis and Marquise is undermined by their mistaken belief that love is subject to one’s slightest whims and desires, and that there is no price to be paid for emotional autonomy. But it is the very paying of that price that makes love stronger and more perfect. Attempting to play the game without following that rule will leave us disqualified before the starting gun has even sounded. And that would be a great tragedy, because, as we know in our quietest and clearest moments, this game is the only one worth playing.

A man who believes that he knows himself is a man who may never really understand anything. Moon is a reminder to all of us that the quest for self-knowledge is not only painful; it is never-ending. After all, “If anyone imagines that he knows something, he does not yet know as he ought to know.”

Cross is doomed (and blessed) to live out his name, carrying the cross of his transgressions until the end of his earthly days. As one of the film's characters tells Cross, "Nobody gets away with murder. No one escapes punishment." That is true for all sin, and thank God for it.

...the Path of Least Resistance always looks good at that first crossroad. But over time, the burdens of sorrow and regret that it slowly adds to our lives prove far more tiring and troublesome than the more difficult choice. The true "long con" is the one we work upon ourselves, seeking ease and success at the expense of the Right and True. That way madness lies.

The sad and dangerous truth is that we increasingly equate love with "eros," habitually confusing the complex, multifaceted reality that lies at the very core of our humanity with a physical, all-consuming passion that burns brightly and gloriously and yet quickly fades. If that's all love is, then why should we be expected to remain standing, and faithful, in the burned-out husk of our once-glorious romances?

Blessed John Henry Cardinal Newman has said, "Ten thousand difficulties do not make one doubt." We must strain and struggle to remember that distinction, particularly in times like these. The dichotomy between the mistrust we now feel in our fellow humans and the trust we must always have in the strength and omniscient power of the Divine Comforter has never been clearer for those of our generation.

Sadly, Higgins treats her like a guttersnipe even when she is dressed like a lady. But Pickering treats her like a lady even when she seems like nothing more than a poor, ignorant guttersnipe. He genuinely cares for her and her well-being—the perfect foil to Higgins' calloused indifference and selfish motivations.

To embrace maturity at the expense of wonder would be a terrible mistake, yet it is a mistake that modern society makes with regularity. Our adult instinct is to reject the fantastical and wonder-filled for more "grounded" pursuits, but the Socratic suggestion that wisdom ushers in wonder should give us pause. As Chesterton reminds us, "The world will never starve for want of wonders, but only for want of wonder." And it is that warning that lies at the heart of The Fall.

This climate of unease and imminent danger runs so deeply through both films, they feel almost like chapters of the same story. And yet, it is in the profound differences between the films' main characters that the kinship between their messages becomes most clear.

Perhaps the most intriguing question raised by the show, however—and it is an obvious nod to Nolan's film—is the very thing which makes one pause when considering the recent trend towards Post-Modern Heroism: What is to be made of the essential (and essentially unchecked) role of vigilantism?

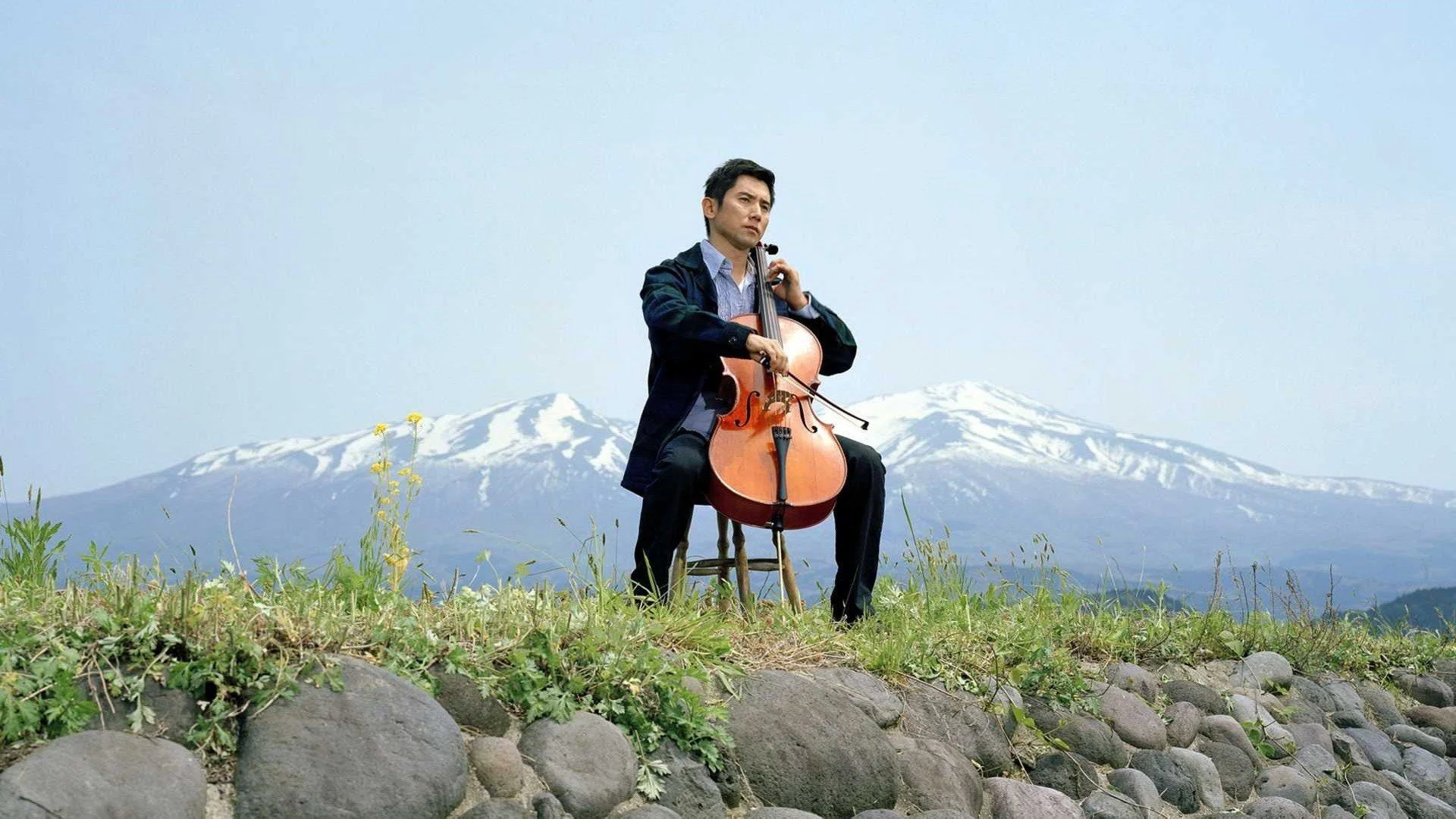

[Kobayashi's] role as nokanshi is primarily a cultural one. But the film is also unashamed and uncompromising in its clear belief that death is far from the end of all things. As one character puts it, "Death is like a gateway. Dying doesn't mean the end. You go through it, and on to the next thing."

Only He was not the savior of a single town; He was the savior of all mankind. Like George Bailey, he is the cause of our joy, the source of all happiness for those around Him. He came into the world on a similarly dark, unwelcoming night to save us all from our own pride and fear. And we know He'll never let it go to his head.

At their core, both films share an important Christmastime message: What we want is rarely what we truly need, and God's actions in our lives rarely fulfill our expectations. And isn't that exactly the story of Christmas? Who in their right minds would ever think that the answer to the problem of sin and evil would be a humble carpenter's son, born in a stable in the dead of winter? Thank God He didn't leave it up to us.

It is at that moment that the hierarchical relationship of parent to child can begin to transform into that which all parents truly desire with their children: a deep and abiding friendship. And that friendship, like any truly profound friendship, can only begin once each sees the other as they truly are.

We are not called to love Him when convenient, or when moved by our emotions, or when He seems to reciprocate our love in a manner and to a degree we deem appropriate. We are called to love always, and completely -- with our whole hearts, our whole minds, our whole souls. Mohammad, in his world of darkness, is not to be pitied; he sees far more clearly than we ever shall.

Contrition is not simply a matter of identification; it is an embracing of the command to "go forth, and sin no more." That understanding of self and willingness to change is the ultimate message of Anderson's films.

Young Michael starts out on the road to Perdition as a child, but he leaves it as a man -- thoroughly rejecting his father’s violent methods and practices, but just as thoroughly embracing his father’s hopes and fears, his beliefs, principles, and the clear moral code that was more important to him than life itself.

As a filmmaker (or writer) tells a story that pushes “outward toward the limits of mystery,” characters that “act on a trust beyond themselves” will follow close behind. And while we may be surprised to see the sun there amidst the bread and circuses, we should rejoice all the more at finding it.

It is the presence of these moments — where God reaches down to remind us of His presence and to raise us up — that makes such films worthwhile. They’re often brutal and difficult, and can feel almost relentlessly depressing. But as one catches sight of the Divine even in the midst of this vale of tears, they are gilded with a new and rewarding light.

Taking the naive optimism of the genre's Golden era and the stylistic cynicism of more recent years, modern filmmakers have found a way to meld the two – an amalgamation that manages to be relevant despite the failing of both of its parents. Perhaps old wine in new wine skins isn't such a bad idea after all.

McCarthy's extraordinary abilities as a writer and director, displayed so marvelously in his first film (the subtle and charmingly quirky Station Agent), are certainly put to the test here. A story that revolves so essentially about the topic of illegal immigration brings some significant built-in difficulties, and one might well wonder if his quiet storytelling-style would survive such a politically charged topic. Thankfully, those doubts are largely ill-founded here; whereas most directors build their political films around the message (see "Stone, Oliver"), McCarthy is more focused on his characters than on their ideologies.

Interestingly, Vargas never again allows himself to dwell on the brutality underlying the film's message of resistance in the face of unjust oppression, scrupulously avoiding nearly every opportunity for violence the story presents him. The penultimate scene in the film, in particular, would seem to call out for a resolution consistent in tone with the opening sequence, but Vargas refuses to take that route, choosing instead a more ambiguous (and finally, more thought-provoking) ending.

Unlike Edward Zwick's strangely inconsistent Last Samurai – a film that deals with a similar time period in Japanese samurai history, yet cannot resist the temptation to portray the "enlightened Westerners" as the ones possessing the final answers – this work demonstrates not only a nuanced understanding of the eroding samurai code, but a far subtler solution to the "problem of progress" that faced Japan in the mid-1800s; a solution whose heart lies in Twilight himself, and in his selfless devotion to his family.

Unlike Nolan's first effort, which seemed to bog down as it neared the finish line – gradually descending into a confusing, clichéd, action-heavy finale – this one will keep you riveted until the final bitter-sweet moment. The film is just short of two and a half hours, but don't bother to bring a watch. You won't be needing it.

The way in which Sabine's disease is so intimately linked to her perception of relationships provides us with an unparalleled opportunity for recognizing the inexplicable, essential role of human dignity in our emotional and spiritual well-being. When Sabine and her struggles are reduced to a problem that needs to be addressed and eliminated, or as a collection of symptoms that need to be treated, she withdraws into the protective shell of her disease. But when her humanity is recognized – when her sister or her caretakers deal with her as an individual, with a full measure of the strengths, weaknesses, talents, and foibles that accompany each one of us individual human beings – she flourishes.

Despite the fairly predictable fashion in which the story unfolds, the film is filled with charming and unexpectedly insightful details. The extraordinary chemistry between Moshe and Malli – praying, arguing, complaining, sorrowing, and coming to love one another more through it all – is the real backbone of the piece, and the nuances explored in their relationship make the film eminently re-watchable. Plus, its finale features a "Come to Hashem" moment that is as satisfying and cathartic as one could possibly hope for.

The fact that philosopher Søren Kierkegaard and Anders Thomas Jensen are both of Danish descent is a particularly interesting prism through which to view the film. Perhaps the Danes are more acutely aware of the apparent contradiction between knowing and believing than we Americans, as Jensen is clearly grappling with many of the same issues that consumed Kierkegaard. His resolution – a leap of faith similar to those present in Kierkegaard's philosophical writings – is ultimately as unsatisfying as that of his predecessor, yet Jensen seems determined to trace Kierkegaard's footsteps down the path of irreconcilable conflict.

The movie's original (and ultimately unused) title, The Eighth Day, is a clear reference to the notion that man's pursuit of genetic perfection is simply an effort to improve on God's seven days of Creation, as well as an equally clear indication of Niccol's own views on the matter. It is a warning for that time when humans will control their own "evolution," and a suggestion that we should be cautious – even fearful – of the consequences of such power. The expectation of flawlessness is a very different thing from the pursuit of perfection.

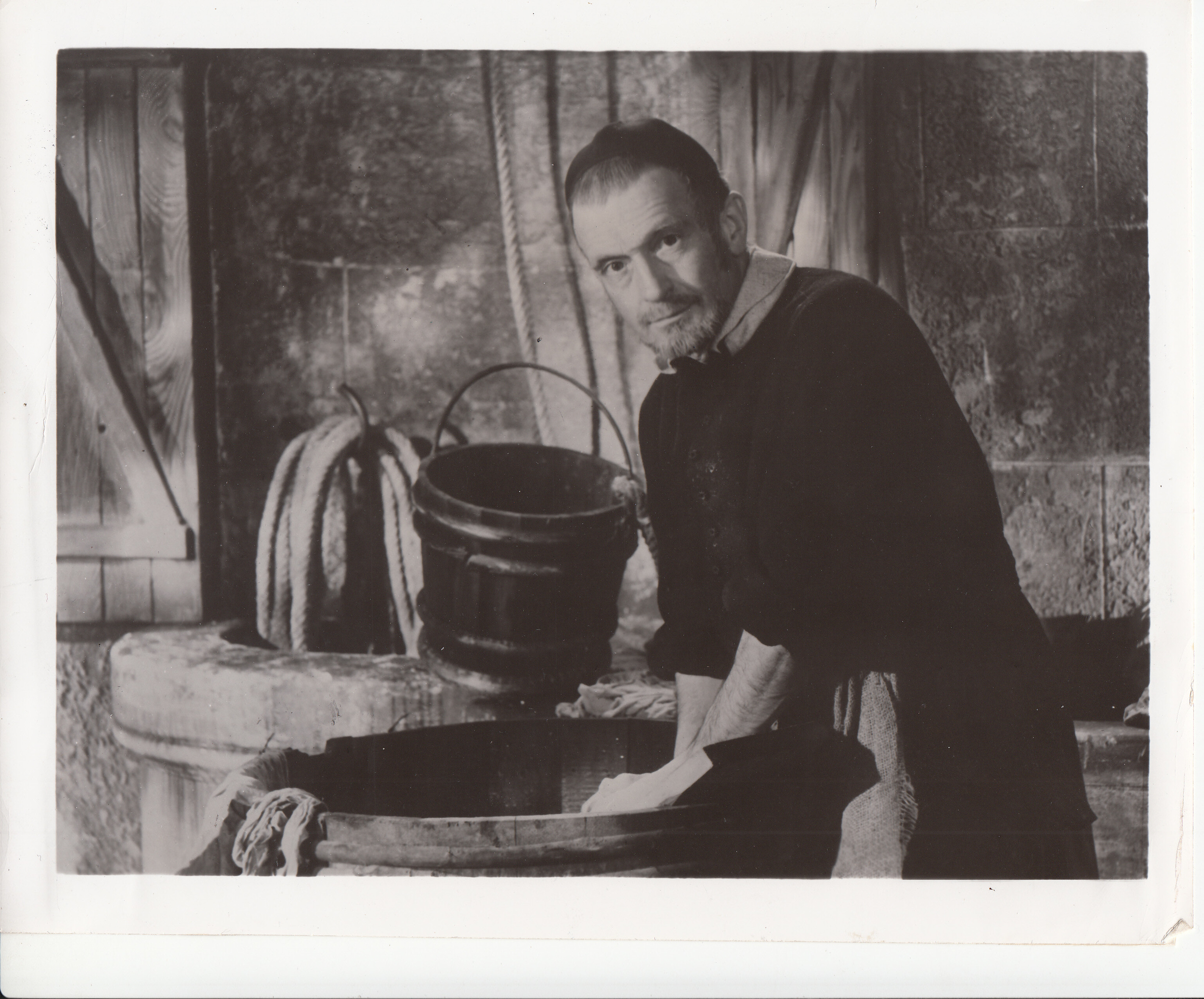

Tarkovsky's Rublev is primarily concerned with the role of (possibly Divine) inspiration in the life of the artist, and with the turmoil and self-doubt brought about when one loses that inspiration. But in Ostrov, Father Anatoli's story revolves around the struggle for forgiveness and sanctification in the life of an ordinary man, highlighting wonderfully the fact that while sanctity is for ordinary people, it is never ordinary itself.

- February 2008

- March 2008

- May 2008

- June 2008

- July 2008

- August 2008

- October 2008

- November 2008

- June 2010

- October 2010

- November 2010

- December 2010

- January 2011

- February 2011

- March 2011

- April 2011

- May 2011

- June 2011

- July 2011

- August 2011

- September 2011

- October 2011

- November 2011

- December 2011

- January 2012

- February 2012

- March 2012

- April 2012

- May 2012

- June 2012

- July 2012

- September 2012

- December 2012

- January 2013

- September 2013

- December 2014

- April 2015

[Baxter] is rejecting his previous failure, and doing it because of what he now knows because of his relationship with Fran. He isn’t expecting a reward, as his departure and packing make abundantly clear. He’s doing it because it’s the right thing, goodness-wise.