Hayao Miyazaki is a rare and indispensible artist.

In a creative industry that flits happily between the brutal demythification and saccharine sentimentalization of childhood, his ability to capture the innocence, exuberance, and boundless imagination of youth is unusual. Watching My Neighbor Totoro, Laputa, or Ponyowith an audience of youngsters is a marvelous experience; their rapt expressions and delighted laughter prove how thoroughly the legendary Japanese animator "gets" children.

Yet it would be a shame to dismiss his gentler work as nothing but childish amusement. Like the Pixar films he has influenced, Miyazaki's creations are both entertaining and enlightening; for him, animation is the lens through which he looks at life, not a way to distance himself or his audience from its lessons.

Spirited Away, widely regarded as his finest work, is the paradigm example of Miyazaki's genius. Blending imaginative (and occasionally unsettling) imagery with a rich tapestry of fantastical creatures, the film recounts the tribulations of Chihiro, a young girl transported without warning from her safe, spoiled life to a vivid "spirit world" of ghosts and sorcerers. Cut off from her over-indulgent parents, bewildered by the inexplicable setting in which she finds herself, she is befriended by a mysterious young boy, Haku, who tells her that the only way to return to her familiar life is to land a job at the mysterious bathhouse that towers above them.

Braving the wrath of the building's proprietor, the spiteful enchantress Yubaba, Chihiro secures employment, becoming an Assistant Serving Girl and immersing herself in the strange world around her. With a bit of amateurish sleuthing, she discovers that Haku is under Yubaba's evil curse, constrained by the sorceress' magical powers to do her dirty work, which puts him in a position of extreme danger.

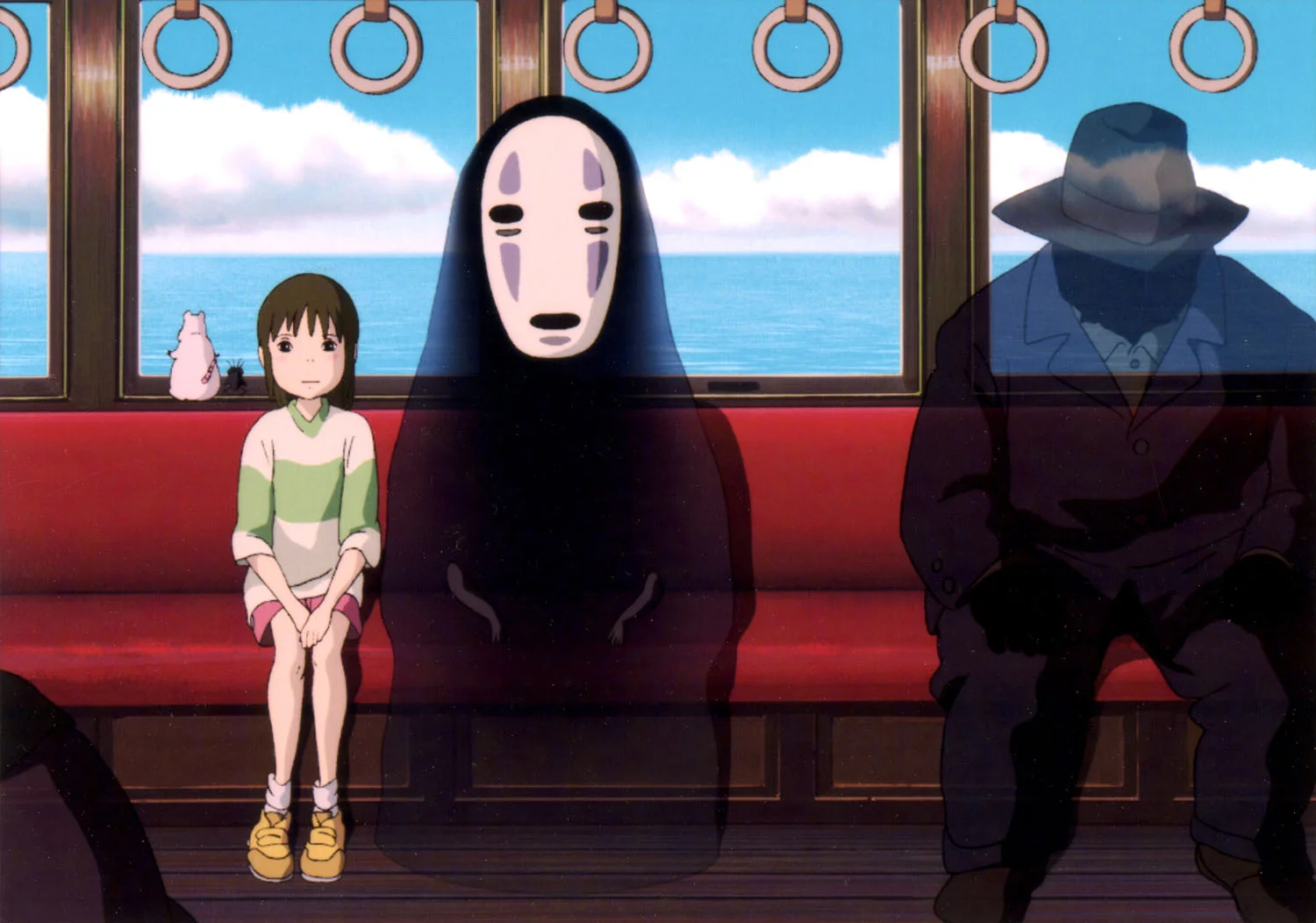

At the same time, she becomes embroiled with one of the house's most problematic clients: a particularly disquieting spirit known as "No-Face." When Chihiro first encounters him, he can barely communicate. His loneliness is palpable, though, and Chihiro attempts to make him welcome. Initially, he seeks nothing more than her company, but his hunger (which is both metaphorical and physical) grows acute, and he begins to consume Chihiro's fellow employees at a truly alarming rate. The gluttonous spirit does more than simply devour his victims: it absorbs them, taking on their characteristics and personality traits, as well.

The situation rapidly grows unmanageable in the bathhouse; Haku's impending doom and No-Face's appalling binge forces Chihiro to step far outside her comfort zone in order to overcome the obstacles before her and return safely home.

Miyazaki's film presents its viewers with an embarrassment of riches. The conflict between Japanese customs and the advance of modernity is lurking just beneath the surface; there is a sense of fond wistfulness behind his pervasive use of traditional Japanese folkloric imagery (pdf). His representation of hard, honest labor as both necessary and ennobling is a too-seldom explored theme, as is the emptiness of the capitalistic, consumerist mentality of Chihiro's parents. The environmental concerns that underlie so many of Miyazaki's stories are found here, too, but their restraint is a key component in setting Spirited Awayapart from its siblings. And the character of No-Face, concealing his true nature behind his traditional Noh mask, is a rich duality—at once representing how dramatically (and incontrovertibly) we are nurtured and shaped by those around us and how quickly our desire for adulation can grow parasitic and all-consuming. In No-Face we are reminded that the best way to rein in our ego is through self-denial, and an acceptance of our state in life.

Yet it is the transformation of Chihiro herself—and the reason behind that profound change—that stands out as the clearest and most important message in Spirited Away.We meet her as a selfish, self-centered young child: the unsurprising product of selfish and self-centered parents, and her first terrifying moments in the Spirit World are all the more difficult for her, precisely because she is so closed off and used to having her own way.

As her days in the bathhouse wear on, however, her motivations grow more clearly admirable. Her desire to rescue her parents, once inextricably linked to her wish to return home, is now driven by a desire for their safety and happiness. Her interaction with No-Face and the other bathhouse patrons grows more genuine. Even the moments spent with Yubaba and her henchmen grow more manageable, as Chihiro matures. And when the time comes for her to choose between her own safety and the life of her dear Haku, her decision is instantaneous and without self-consideration.

We all have a bit of the Selfish Chihiro in us, waging an endless battle against the urge to place our wants before the needs of those we love. But Miyazaki's masterpiece reminds us that we must never stop fighting that urge—that it is only in subsuming our desires to the will of Another that we will find true freedom.

It seems that we can always do with a bit more spiriting away.