Life in a household of six boys often feels relentlessly jumbled and overwhelming. The wall of sound that greets me on my return home each day; the coughing, congestion and continual runny noses; the endless cycle of feeding, cleaning, and caring for this beloved brood of mine—my wife and I find ourselves willing-yet-worn-thin on the Sisyphean waterwheel of our sons' lives.

In this context, I recently had the chance to watch Tom McCarthy's largely overlooked Win Win for the first time, and was bolstered by its gentle encouragements. Like McCarthy's previous two works (The Visitor and The Station Agent), this film is deceptively subdued, concealing its considerable insights behind the mundane activities of ordinary, unexciting protagonists. This time, McCarthy and his co-writer, long-time friend Joe Tioboni, dipped into their own pasts to tell the story of Mike Flaherty, a small-town lawyer struggling to balance his failing law practice against the needs of his burgeoning family, and his responsibilities toward the inept high school wrestling team he coaches in his "spare time."

Testing the viability of his "elder law" practice, our middling lawyer fastens upon a wealthy, dementia-ravaged senior as a means of ensuring the financial future of his family. Convincing a judge that he supports the fading Mr. Leo's desire to live out his waning days in the comfort of his own home, Mike instead banishes the old man to the town's senior care facility and pockets the funds designated for his monthly care.

The unexpected arrival of his client's troubled grandson, Kyle—a gifted high-school wrestler with a history of emotional problems—muddies the waters considerably. Moved by the boy's efforts to escape from a troubled past (and well aware of the gigantic boost he provides to the wrestling team), Mike welcomes Kyle into his house, and he quickly becomes an integral part of the Flaherty family. But when Kyle's deadbeat mom attempts to reclaim her father's wealth, Mike finds himself playing an increasingly dangerous game of deception.

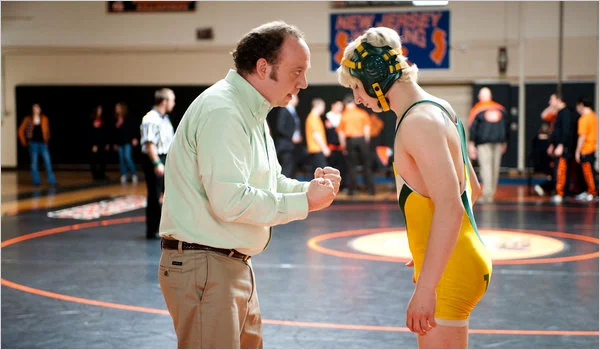

The film is noteworthy for the wonderful performances of Paul Giamatti as Mike and Alex Shaffer as Kyle, and for the extraordinary subtlety and honesty of its writing. McCarthy's knack for capturing instantly knowable characters is evident in all three of his films, and I'm amazed anew every time I see it.

But Win Win is perhaps most memorable for its portrayal of a character we rarely see and even more rarely appreciate—a man overwhelmed by the day-to-day details of a life he wouldn't trade for anything; a man struggling to do the right thing, terrified by the prospect of failing his family, yet battling against the temptation of the "easy way out;" one who falls repeatedly, but is man enough to recognize when he has failed. A film overflowing with worthwhile "take-away messages," it is above all a refreshing reminder that an ordinary man struggling to live his life as well and faithfully as he is able will have a profound impact on those closest to him.

Mike's worth is not measured by his barristerial success or by the accomplishments of his wrestling team. It is measured far more meaningfully and subtly—by the quiet influence he wields over his family, his friends, and over the young, desperate boy who stumbles across his path. It is his willingness to pour himself out for them each and every day that most clearly manifests his worth; a willingness rarely recognized and always under-appreciated, yet one that will prove more perfective of him than anything else he could attempt.

This is a vital and timely reminder for often-frayed fathers like me, who struggle daily with what seem like the irreconcilable conflicts between Mary and Martha. Like many parents, I yearn for a deeper, truer, more peaceful friendship with Christ. Yet I am so distracted by the constant needs of my boys that a relationship of depth seems well nigh impossible. Is there anything more frustrating than reaching the end of Mass and realizing that while your body was most definitely present, you were barely there at all?

If Mary chose the better part, what is to be done with Marthas like me—parents whose earnest attempts at spiritual growth succumb to the non-stop barrage of our children's needs?

The mistake, perhaps, is in seeing them as competing actions, or even separate ones. The longer I am a father, the more I am convinced that prayer and parenting are not disparate activities to be balanced; they are one-and-the-same. Properly understood, raising my children is cultivating a personal friendship with God. I'm not "wasting my time on less important things when I should be focused on the One that really matters." Instead, I'm sitting at His feet even as I chase my beloved, boisterous 16-month-old through the Holy Rosary cry room, or as I wade through my umpteenth Excel spreadsheet at work.

Mary and Martha, so often relegated to opposite sides of the spiritual spectrum, would doubtless recognize that I am not focused on my kids instead of God; I'm focused on them because of Him. And that praying through the distractions of my family does not render my devotions powerless, but imbues them with more power than I could ever have achieved on my own. Was it not He Himself that commanded us to let these little distractions come to Him?

Win-Win speaks to all of that, reminding fathers like me that the struggles we undertake on behalf of our loved ones are the surest manifestation of our love for them. Paradoxically, it is our willing embrace of their terrifying entanglements that will finally bring us peace.