WARNING: This review reveals plot points perhaps best experienced in person. For those who have not yet seen The Son (Le Fils) from the Brothers Dardaine, it can be found on Netflix's Watch Instantly.

As Lent draws to a close, I always find myself searching for a film to assist me in my preparations for Holy Week. This annual task has let to such gems as Ostrov, The Passion of Joan of Arc, and The Ninth Day, providing me with ample food for thought and soul during my Passiontide journey.

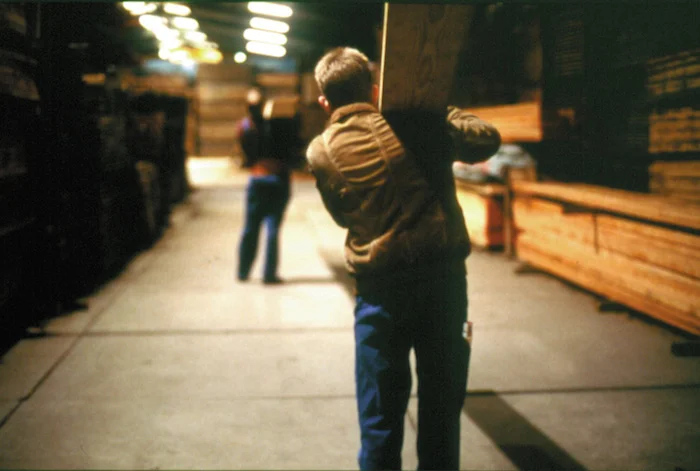

This year's suggestion, The Son (Le Fils) from the Belgian brothers Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne, is both a revelation and a challenge. It follows the outwardly mundane life of Olivier, a middle-aged carpenter weighed down by a deep and devastating secret. (And I mean that "follows" quite literally, for the entire film is shot in a "hand-held," claustrophobic style, the probing camera rarely more than a foot or two from Olivier's face and shoulders.)

The story itself is deceptively simple: Francis, a troubled youth only recently released from prison, is brought to Olivier's shop for rehabilitation into the workforce. Citing an already-excessive number of apprentices, the carpenter refuses to accept him, but abruptly changes his mind, agreeing to train the boy. All too soon, the reason for his sudden change of heart becoming clear: when Francis arrived, Olivier instantly recognized him as the one responsible for the death of Olivier's son a few years before.

Brought face-to-face with the reason behind his lonely, sorrowful life, the carpenter grows obsessed with the boy, secretly following him throughout the city. Francis, unaware of his mentor's spying and of the destructive role he has himself played in Olivier's life, begins to grow attached to the quiet carpenter; he asks Olivier to become his guardian. Taken aback by this unexpected signal of trust, the long-suffering man finds himself torn between the thirst for vengeance and his genuine desire to forgive the troubled young boy. Can he move beyond the pain and heartbreak Francis has caused him, or will his halting attempts at mercy fall the final victim to the tragic events put in motion so many years before?

Yes, the story sounds contrived, and the unusual stylistic approach is sure to prove off-putting to some, but there is something coiled and unrelentingly suspenseful about it, thanks to the director-brothers' shrewd way of using our own preconceptions against us.

When Olivier first begins to spy on Francis, one springs quickly to the ugliest, most prurient explanation for his interest. Yet as the audience learns of the violent history underlying the protagonists' relationship, that potentially distasteful account is quickly erased, overshadowed by Olivier's exhausting struggle between leniency and vengeance. Ordinary, everyday tools take on ominous possibilities entirely at odds with their commonplace reality—the shop's table saw could easily be turned to a darker purpose; the pile of planks in the lumber yard would crush the young lad and easily be attributed to an unfortunate accident. Countless opportunities for revenge present themselves. But Olivier refuses to act on them.

In fact, the question of whether he will ever act upon his vengeful tendencies is one that exists almost entirely in the minds of the audience. The notion of revenge, while ever-present, is never at the forefront of Olivier's mind. He is after a completely different kind of retribution.

In one of the film's most pivotal scenes, Olivier's ex-wife, Magali, discovers Francis' identity. Devastated by Olivier's willingness to reach out to the very person responsible for their suffering, she berates him for his attempts at reconciliation: "Nobody would do that," she says. When he agrees, she demands "So why you?"

His response? "I don't know." And neither do we.

The notion of turning the other cheek is almost impossibly difficult. We do it because we have been commanded to, but we do it grudgingly, and with resentment. "We're being good," we say, "but we're not going to be happy about it."

How poorly we have learned the lessons of Holy Week.

Olivier's inactivity is a surprise to us only because we expect him to lash out against the evil that has been done to him. Even he is unable to understand why he wishes to forgive the young Francis; he only knows that he must try. I could not watch his unfathomable desire to bestow mercy without thinking of another Father, reaching out to forgive those very villains who took the life of His most precious Son.

Like Olivier, our Heavenly Father lost His only Son at the hands of others. And like Olivier, He embraced His son's killers with a love so far beyond all human comprehension that we find ourselves astounded by it. "Nobody would do that," we say. "And even if someone did, He would never be able to understand why."

But God's forgiveness is even more absurd than Olivier's, for His Son's killer was not (nay,is not) a single, troubled young man. It is an entire race of fallen creatures—a race as obdurate and ungrateful in its rejection of His proffered grace as it is in need of it.

Yet He takes us back to Him even after the brutal betrayal of the Cross, and He has done it every moment of every day since that afternoon on Calvary. God does not do it because He needs to "move beyond" the Cross; He does it for no other reason than our own salvation. He has nothing to gain, and we have everything. How absurd and all-consuming is God's forgiveness; how impossibly unlike human forgiveness.

Let us thank Him for it.