To misquote the old Aesopian saw, familiarity breeds complacency—a truth nowhere more painfully illustrated than in the classic Ealing Studios film, The Man in the White Suit.

Set in the textile mills and factories of early 20th-century England, the film tells the story of Sidney Stratton (Alec Guinness), an eccentric, secretive young scientist obsessed with creating the perfect artificial fiber: a synthetic polymer that will never wear out or deteriorate, rendering all other textiles obsolete. His brilliance is unquestioned; as he anxiously reminds nearly anyone who will listen, he once had "a first and fellowship at Cambridge." But his willingness to go to any lengths to further his research, including surreptitiously acquiring and spending massive amounts of his employers' funds, has made him nearly unemployable in his field.

Dismissed from his umpteenth job as a result of his financial shenanigans, Sidney remains convinced that a solution is near. Impatient to continue his work, he accepts a janitorial position at the Birnley Factory, one of the industry's finest. Once there, he finds himself unexpectedly befriended by several of the local laborers, who embrace his eccentricities with gruff, kind-hearted joshing and bestow upon him their highest honor: an invitation to participate in their never-ending labor disputes with the factory owner. Further emboldened by a change encounter with the owner's daughter, Daphne (Joan Greenwood), Sidney insinuates his way into the Birnley laboratory and finally (shockingly) conducts a successful experiment. As promised, the resulting fiber is indestructible, impervious to dirt, and dazzlingly, unimaginably white.

Sidney's boss, Alan Birnley himself, is elated at his young Wunderkind's success, eagerly anticipating the massive financial windfall that awaits him as a result of the groundbreaking research. Other factory owners in the area, however, are far less enthused. Recognizing the unique polymer as a threat to their continued existence, they band together in an effort to suppress the breakthrough.

Despite Daphne's best efforts to convince him of the nobility of his vision, the doubts cast by his fellow workers are crippling. From there, the story weaves its way to its final, unsurprising conclusion: When Labor and Capital are allied against you, Idealism is of small comfort.

The four films Guinness made under the Ealing Studio banner are some of the finest of his career. But what sets The Man in the White Suit apart from the others is its stark, almost brutal tone. Billed as a "satirical comedy," Suitcertainly has its moments of levity. Yet despite its self-proclaimed hilarity, it is not a comedy; it is a tragedy. The three others—The Ladykillers, Kind Hearts and Coronets, and The Lavender Hill Mob—all feature criminals who are hilariously (and justly) punished for their transgressions. But The Man in the White Suit is punished for his virtues, not for his vices, preyed upon by the very friends he most expected to support him. While Guinness is as infectiously droll and charming as the material will allow, his eventual downfall at the hands of the suddenly-hostile factory workers is a bitter pill to swallow.

The bizarre exploits and cacophonous inventions that populate the first act are both engaging and genuinely humorous. By the time the finale arrives, however, the film has tackled much larger issues than one might have expected from a comedy—a stinging sociopolitical critique that pits the "advancements" of the industrial age against the hypothetical (yet believable) improvement of an entire class, highlighting the peculiar way in which humanity reacts to progress.

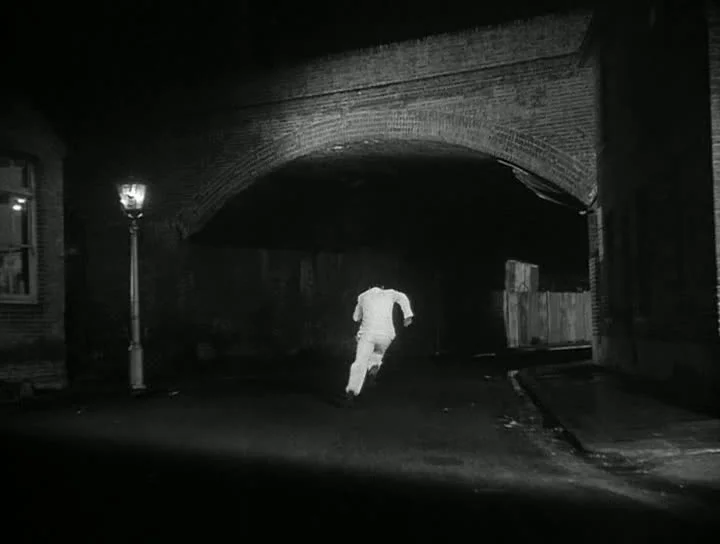

When Sidney first dons his unnaturally luminous suit, Daphne laughingly calls him "a knight in shining armor," a description that is more accurate than either of them realize. In the finest chivalric tradition, the young scientist is driven by a desire to aid others, his soul as white and untainted as the material he wears. When the very friends he is struggling to help reject his efforts, he is bewildered and lost; for the first time, his drive fails him, damaged by the very people who gave it life. To be rejected by the capitalists and factory owners came as no surprise; his goals and ideals were always in conflict with theirs. But to have his work rejected by those it would benefit most? To have his heroic vision received as nothing more than an idle tilting at windmills? That was a cruel (if not entirely unexpected) blow.

Familiarity breeds complacency.

The intended recipients of Sidney's largess are comfortable with their way of life and deathly afraid of anything that may change it. They fear losing their livelihoods (arduous and soul-crushing though they be), clinging instead to their ordinary, inexplicably comfortable routines, even in the face of a true godsend. Our hero is defeated not by Labor or by Capital; he is defeated by the profoundly human tendency toward inertia. A life spent slaving away in a textile factory might not seem like much of a life, but at least it doesn't require one to make difficult decisions, or strike out into an unknown and challenging new world.

Nowhere does this tendency for complacency show up as regularly (or as dangerously) as in the spiritual life. All too often, we grow habituated to our little routines, soothing ourselves with the easy, comforting rhymes of oft-repeated prayers. And while familiarity itself can be a blessing, we must be alert to the very real danger of stagnation. We need something to shake us out of such familiar territory from time to time—something (or Someone) to remind us that we are far from finished products, and that it is only by continually pushing ourselves that we can grow.

But isn't that exactly why we have Lent?