To say that death has become an unimportant part of our cinematic vocabulary would seem like the height of absurdity. The body count from Sly Stallone's two latest features alone could easily populate a small country, and there are few plot points so frequently used as: "unexpected death of parent/sibling/lover throws protagonist into deep, expressive turmoil." Yet shuffling off this mortal coil, while omnipresent, is rarely the focus of much cinematic attention; all too often, movie mortality finds itself cast in a limited supporting role. Death is primarily seen as either the intended-yet-incidental consequence of Our Hero's latest spectacular feats of physical prowess and marvelously unbelievable bad-assitude, or as an important-but-rapidly-receding stepping-stone on the pathway to more emotionally resonant story elements.

This is not unusual. As a culture, we are mightily reluctant to dwell on death. The Grim Reaper walks among us with such alarming and inexorable regularity that we are inclined to pay him no more heed than necessary. The day of reckoning will come to all of us soon enough; why dwell on it before its terrifying arrival? Our films reflect our attitudes—the dreadful specter is ever-present, but we go to great lengths to avoid looking at him directly.

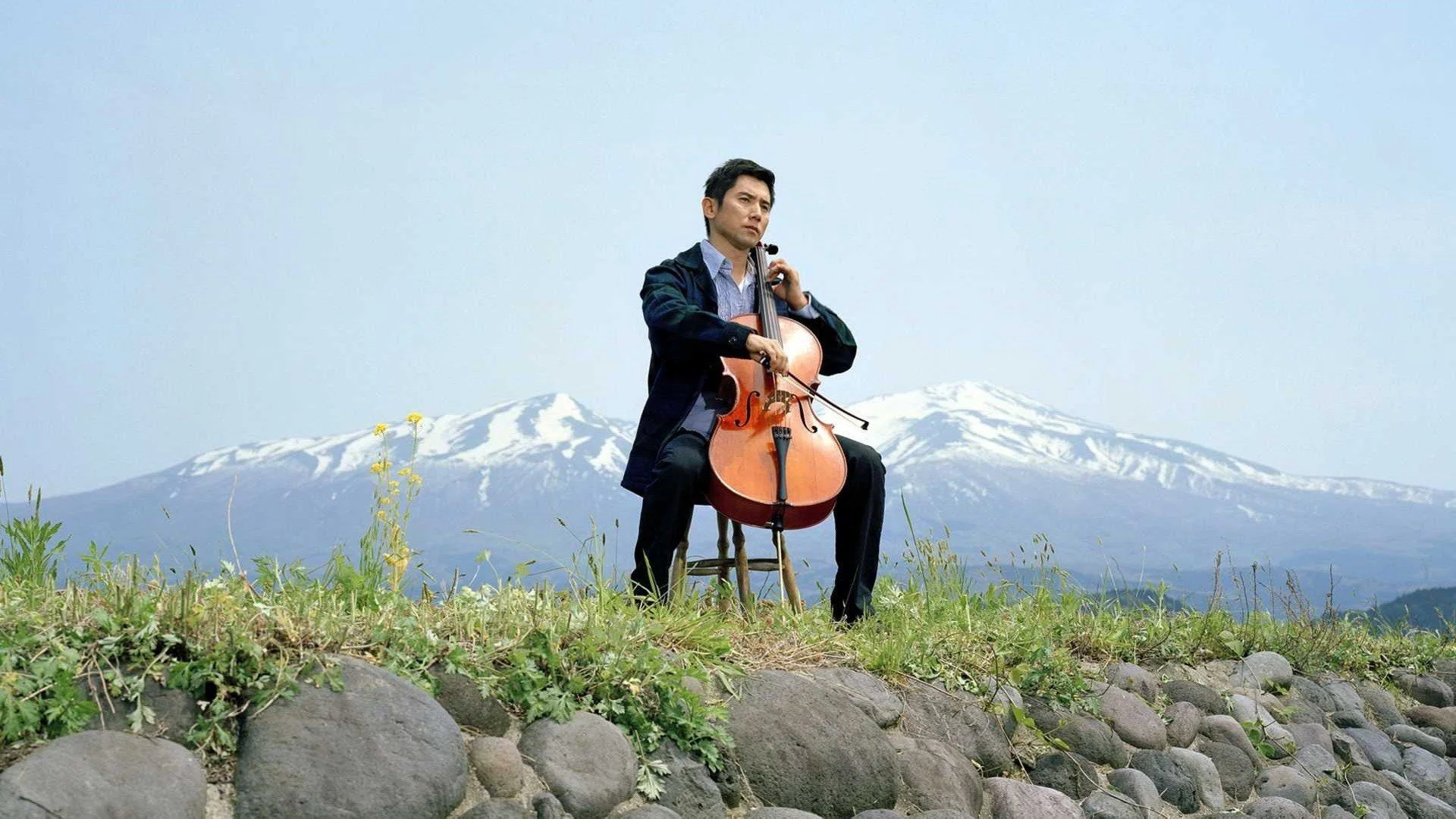

A wonderfully noteworthy exception to this understandable reticence is Japanese director Yôjirô Takita's extraordinary and unexpectedly Oscar-winning film, Departures (Okuribito). It tells the story of young Daigo Kobayashi, an aspiring concert cellist, who finds himself forced to return to his birthplace when the mid-level orchestra which has employed him is dissolved. Accompanied by his wife, Daigo reluctantly searches for work, all too aware that his musical skill is insufficient for regular employment. Responding to a peculiar newspaper advertisement, he finds himself offered the job of a nokanshi (encoffiner)—someone who travels to the homes of the recently deceased to perform the ceremonial, ritualistic burial preparations in the presence of the departed one's grieving family members.

Initially, Kobayashi is overwhelmed and horrified by his new calling. The first corpse he is summoned to encoffin is the body of an elderly woman who passed away a full two weeks before being discovered, and the physical and emotional toll of ministering to her mortal remains are almost too much for him to process. But as he watches the extraordinary work of his employer, Shōei, he grows to more fully appreciate the peace and comfort the cleansing ceremonies bring to those who see them. There is a beauty and artistry to the services he and his fellow nokanshi perform; as he takes a more active role in the business, the instances of grief and bitterness he experiences in the families to which he ministers are gradually replaced by moments of fond farewells and even quiet affection and joy. Unfortunately, his friends and family are less enthusiastic over his new-found work.

Encoffining is looked upon by many as "unclean," and those who perform its rituals are shunned. Daigo's unwise decision to keep his wife, Mika, in the dark regarding his role as nokanshi soon leads to an emotional confrontation. Aghast when she discovers what he has been doing, Mika demands that he either give up his new-found role or risk losing her altogether. Torn between his love for his wife and his recognition of the good he is doing through his labors, Daigo hesitates over his decision, and Mika leaves him. Distraught, he seeks solace in his work, his newly-discovered usefulness, and (perhaps most importantly) his music.

But the separation is not to last. When Mika returns a few months later, filled to bursting with the good news that she is pregnant, she is confident that the impending arrival of his child will shame the father-to-be into accepting a more "normal" line of work. Kobayashi, who has harbored a deep-seated resentment against his own dead-beat father for many years, struggles to cope with his conflicting emotions as his personal life becomes even more closely intertwined with his professional activities.

In a resolution that is wonderfully apt (if perhaps a trifle too tidy for complete plausibility), the young couple becomes drawn more-closely together by the very ceremonies that previously pushed them apart. After a lifetime of anger and denial, the young comforter finds himself in need of comforting, and what has been nothing more than a ritualistic exercise in the past becomes deeply personal. In the striking final scene, life and death are brought together into a wonderful simultaneity, as both husband and wife are transformed through their grief and resignation.

The story is "spiritual, not religious." Kobayashi participates in ceremonies for nearly every denomination, suggesting that his role as nokanshi is primarily a cultural one. But the film is also unashamed and uncompromising in its clear belief that death is far from the end of all things. As one character puts it, "Death is like a gateway. Dying doesn't mean the end. You go through it, and on to the next thing." For a society increasingly obsessed with extending life no matter the cost, the characters' matter-of-fact, fearless acceptance of their wholly natural worldly demise is both refreshing and inspiring.

We humans, despite our best efforts to the contrary, struggle constantly against the notion that death is the conclusion of a story, rather than the gentle pause that comes at the end of a chapter. No wonder we are terrified and undone by its impending arrival. But as "Departures" reminds us so beautifully, it is the recognition of death as a single step along the endless path of life—an understanding that the span of our worldly days can only be properly understood in the context of a far greater work, penned by a far greater Writer than ourselves—that lies at the heart of our ability to accept it without fear.

May we all be granted the comforting grace of this understanding as we draw ever-nearer to that gate which awaits us all.