It's easy to see why writers and directors are attracted to remakes.

While studios like them for the built-in audiences, low risk factor, and negligible pre-production, the "creatives" are often motivated by less economic considerations. They like the chance to introduce new generations of moviegoers to the works that most influenced them, and the chance to take the original ideas in new and unexpected directions is simply too tantalizing to ignore.

The 2008 remake of the legendary 1951 film The Day the Earth Stood Still is a perfect illustration of this dynamic—a film paying clear homage to its storied predecessor, while just as clearly exploring thematic material only hinted at in the original.

The outline of the two films is essentially the same: Klaatu, a mysterious extraterrestrial being, arrives on Earth with a message of grave importance, only to be violently detained by a fearful American populace. Befriended by Helen Benson, an altruistic young widow quietly struggling to raise her son in an increasingly tumultuous world, Klaatu recognizes that there may be more to these humans than he and his fellow extraterrestrials assumed. With the help of Helen and her friends, the otherworldly messenger completes his mission and returns to the skies. His departure is a clarion call for humanity to repent of its wickedness and reform its ways.

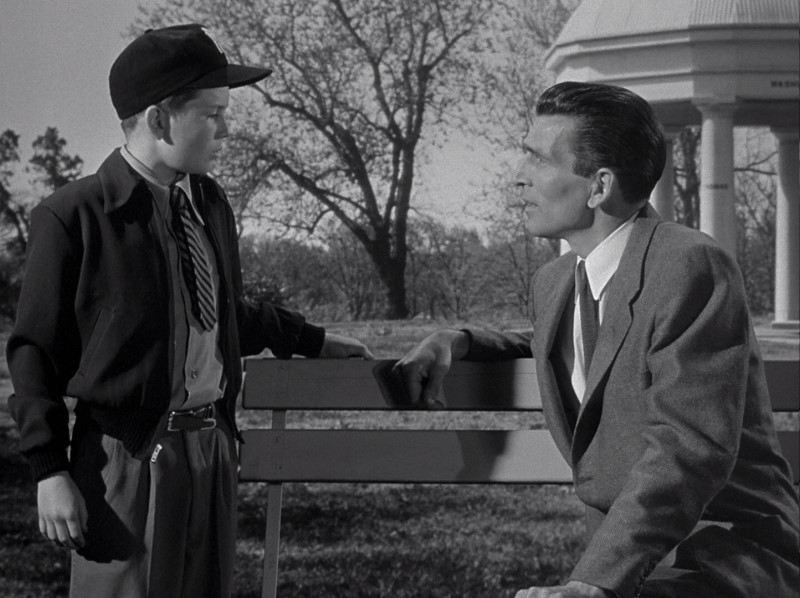

The similarities between the original and remake run deeper, however. In both films, Klaatu remains one of cinema's most striking Christological symbols. In the 1951 version of the film, Klaatu's (Michael Rennie) assumed name—Carpenter—hints at the imagery to come, but the film's finale leaves no doubt: Struck down by an angry and irrational mob, Klaatu is resurrected and ascends into the heavens with a warning that mankind must live well or suffer the consequences.

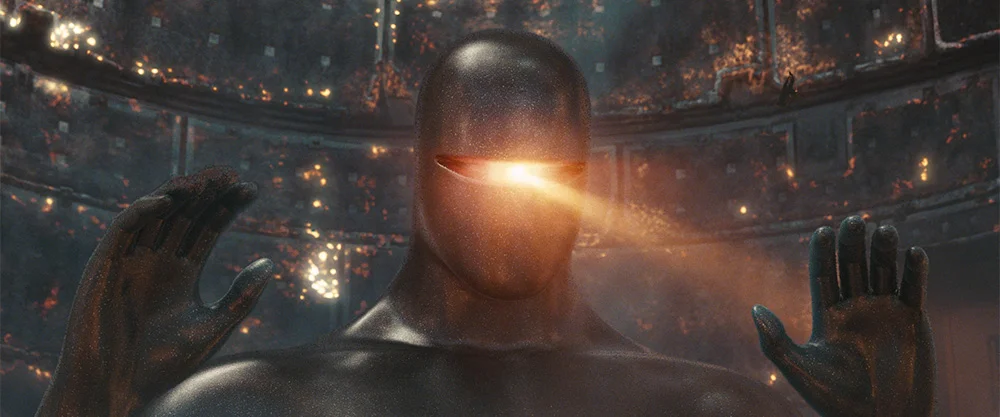

The "old wine in new wine skins" approach of the remake preserves the Christ-imagery but focuses more on Christ's incarnation than His resurrection. Its Klaatu (Keanu Reeves) is not a humanoid life form of unknown origin but a mysterious being whose true appearance is too terrifying (or wonderful) for humans to bear. Described by the film's creators as "an alien in a human body, not an alien with a human body," the new Klaatu accepts his human form as a necessary part of carrying out his mission, eventually sacrificing that very form for the sake of all mankind.

While similarities between the two works are undeniable, differences abound. The 2008 retelling is action-and-effects-driven, depriving it of much of the introspection that remains the hallmark of the original. The decision to highlight mankind's environmental transgressions rather than the war-mongering ones underscored in 1951—no doubt an effort to replicate the cultural relevancy of the original, while acknowledging the radically different era in which we now live—runs the risk of alienating those audience members less convinced of our proximity to Earth's "tipping point."

But perhaps the most dramatic difference between the two films is best demonstrated in how they portray that moment when the Earth finally does stand still. In the 1951 film, the event sounds a stern, Damoclean warning—a message to the world that Klaatu and his fellow extraterrestrials are benevolent-yet-unyielding dictators, that their power over the future of mankind is absolute, and that remorse and transformation are the only way to avoid the ultimate chastisement. In the recent remake, the stillness of the Earth is not a warning; it is a sign of a miraculously forestalled apocalypse. Rather than a threat of impending doom, it is a rainbow that signals the passing of a terrible deluge.

The new Klaatu is no prophet crying out for repentance; he is an avenging angel sent to mete out harsh justice on a race gone hopelessly astray. Yet he is also an angel transformed by his experiences and by the undeniable beauty and self-sacrifice he has seen on Earth. When he first arrives on the planet, his objective is nothing more than the purgation of its most dangerous scourge: humans. The compelling argument put forth by Helen's scientist friend ("It is only on the brink that people find the will to change; only at the precipice that we evolve") leaves him cold when it is first presented. But it is that very argument which returns to him during the film's climactic moment—a revelatory scene in which he recognizes his own proclivity for the prideful destructiveness of which mankind stands accused, and yearns for that transformative self-sacrifice that is such a uniquely human trait.

Klaatu's transformation, a departure from the themes and ideas expressed in the original, highlights an essential element of the human dynamic. On the one hand, we have the 1951 film: a dark, silver-lined examination of the human tendency to violence and selfishness, a call to recognize that tendency, and a plea to transform ourselves through that recognition. It is a reminder that our fallen human nature is profoundly self-destructive, and that we must often use any means necessary—even fear of punishment—to overcome such dangerous inclinations.

The remake, on the other hand, while acknowledging the truth and eternal relevance of our brokenness, chooses to focus on an aspect of our lives that is just as true, and just as essential: our God-given capacity to rise above our fallen humanity. In a world where sin and suffering are omnipresent and all too real, we can ill-afford to lose sight of the beauty and redemptive power found in these "better angels of our nature."