Frankenstein's got nothing on Hollywood.

The earnest and "enlightened" efforts of Shelley's Promethean doctor cannot be ignored, but really, how hard could it be to galvanize an assortment of previously-used body parts into exactly what they were before—a body? What sort of challenge is that? When it comes to stitching disparate elements into a single being, Dr. Victor Frankenstein is a bit of an amateur.

For Hollywood, however, such combinations are old-hat. Since the industry's earliest days, its dream-weavers have fused discordant parts into coherent wholes. For many, a quick, disconcerting trip through the demo reels of such SFX powerhouses as Stargate Studios is all that is needed to remind us of just how rarely things are what they seem in the cinematic world.

Take Seraphim Falls, for example. A full-fledged entry into the "Revisionist Western" trend, it is co-written and directed not just by a newcomer to the Western genre, but by a feature-film neophyte—David Von Ancken—whose previous directing experience was limited to TV shows and shorts. Set in the mountains of New Mexico, it features lengthy sequences shot in Oregon and California, taking its audiences from a snowy mountaintop to a parched desert basin in the course of a few days—all, ostensibly, without ever leaving the Ruby Mountains. The messy aftermath of the American Civil War serves as impetus for many of the film's events, yet the script's stubborn refusal to directly tell (or show) this back-story covers the film's first two acts with a haze of uncertainty. To make matters even more complicated, Von Ancken cast two instantly recognizable Irish superstars as the story's Grey and Blue antagonists: Pierce Brosnan and Liam Neeson.

Bringing life and unity to this rag-tag band of contradictions is no small accomplishment, yet the most memorable conflation produced by Von Ancken's Frankensteinian efforts is not technical or artistic; it is metaphysical.

On the surface, the film is a straight-forward "chase-and-revenge story." It opens as Gideon (Brosnan), a Union captain-turned-trapper, pokes his campfire in an effort to find some warmth in the snow-covered landscape of New Mexico. Suddenly, shots ring out through the chill air, and Gideon spins away from the fire with a bullet in his arm. Shaken, the wounded trapper grabs what little he can and flees, leaving the bulk of his possessions behind. Plunging across a raging river, he pauses just long enough to extract the slug from his shoulder, eventually concealing himself in a nearby tree to await the arrival of his attackers: a team of bounty hunters led by Morsman Carver (Neeson), a former Confederate officer who has sworn to hunt down and destroy Gideon no matter the cost to himself or his followers.

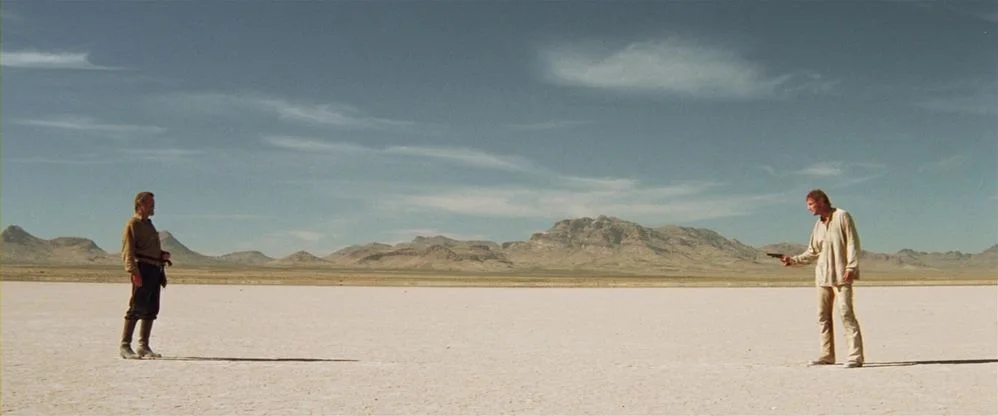

As the pursuit continues down the snowy mountainside to the desert below, Gideon and Carver meet a wide variety of Western stereotypes: cunning mountain men, railway construction workers (and their suspicious Irish foremen), a trio of reckless young bank robbers, a wagon train of religious fundamentalists, and an exceedingly peculiar snake-oil saleswoman. For all the clichés, though, each encounter with these characters helps to reveal a bit more of the dark secret that binds the two men together. Finally stripped of their physical and emotional defenses, Gideon and Carver come face-to-face on the barren desert floor, forced to confront the tragic event that has turned them so violently against one another. Which of the two will embrace the path of revenge, and which will find peace from his spiritual struggles?

When the film was first released, much was made of its spectacular visuals (courtesy of Oscar-winning cinematographer John Toll); the surprisingly American performances of its Irish leads; its starkly violent, revisionist tone and moral ambiguities; and its unmistakably spiritual undercurrent. Much was also made of the sparseness of its plot and its ham-fisted and confusing attempts at allegory. Both sides of the critical divide have ammunition aplenty; the film is probably best described as a promising (even a noble) misfire. But despite falling short of greatness, there is much to recommend it to fans of the Western film and redemptive tale alike.

The film's title is itself a thought-provoking curiosity: could the easy step from Seraphim Falls to "Fallen Angels" possibly be an accident? Where exactly are Carver and Gideon conducting this hunt, anyway? Limbo? Or is it Hell itself? Could the film be understood as Dante's Inferno in reverse, its protagonists clawing their way from the frozen Ninth Ring of Treachery towards eventual salvation?

It is the salvation part that gives the film a memorable topspin, as it comes down to a truth that is so obvious it usually escapes us: we all hope for mercy, but justice must come first, or mercy is simply not possible.

The film's recognition of this truth, which becomes so fundamental to the lives of its protagonists, is the true gem. Mercy and Justice are not "Either/Or," they are "And."

We often find ourselves thinking of justice and mercy as two sides of the same coin, fervently hoping that the coin "comes up Mercy" on the Day of Judgment. To paraphrase Hosea, it is mercy I desire, not justice. In fact, if we could get the awkward question of justice off the table altogether, I'm sure the Final Judgment could get along swimmingly without it.

Yet what can one possibly mean without the other? We must recognize the vast gulf between our actions and what we could and should have done, before God can offer mercy.

In the Gospel, the prodigal son not only recognized his great folly; he asked his father to deal with him justly: "I no longer deserve to be called your son; treat me as you would your servants..." Yet it was his very desire for justice that permitted the father to show his son such profound mercy.

How can God forgive someone who does not recognize their own need for forgiveness? Sure, a "debt" could be paid, but what would that payment mean if there was no spiritual transformation to accompany it? We must be transformed if we are to be perfected, yet there is no transformation without recognition and acceptance of our own personal, insurmountable failings.

And there is no way to recognize those failings without first embracing Justice.

Shakespeare says that humans are most like God "when mercy seasons justice," and perhaps he's right. But we are most dear to Him when our desire for justice seasons our desperate pleas for mercy.

For it is only once we want Justice that we can truly get Mercy.