On the wall above my desk, there hangs a home-made plaque with this Chesterton quote:

For a plain, hard-working man the home is not the one tame place in the world of adventure. It is the one wild place in the world of rules and set tasks.

I love this quote. Not because my home is particularly wild — as least no more wild than one would expect from a place populated almost entirely by boys. And not because my workplace is mindlessly, soul-suckingly repetitive — in fact, I sometimes wish it were a bit more regulated; I’m not always the sort of person who should be allowed to play (or work) unsupervised. I love it because it reminds me of something I too often forget:

“Ordinary” and “Mundane” are easily equated, but to think them the same is a grave mistake.

As someone who falls regularly and easily into the trap of devaluing the “ordinariness” of both work and home life, I was particularly struck by this stumbling block as I worked my way through the latest Studio Ghibli film: Goyo Miyazaki’s From Up on Poppy Hill, which received a typically-limited release in the States earlier this year, but is at last available on DVD.

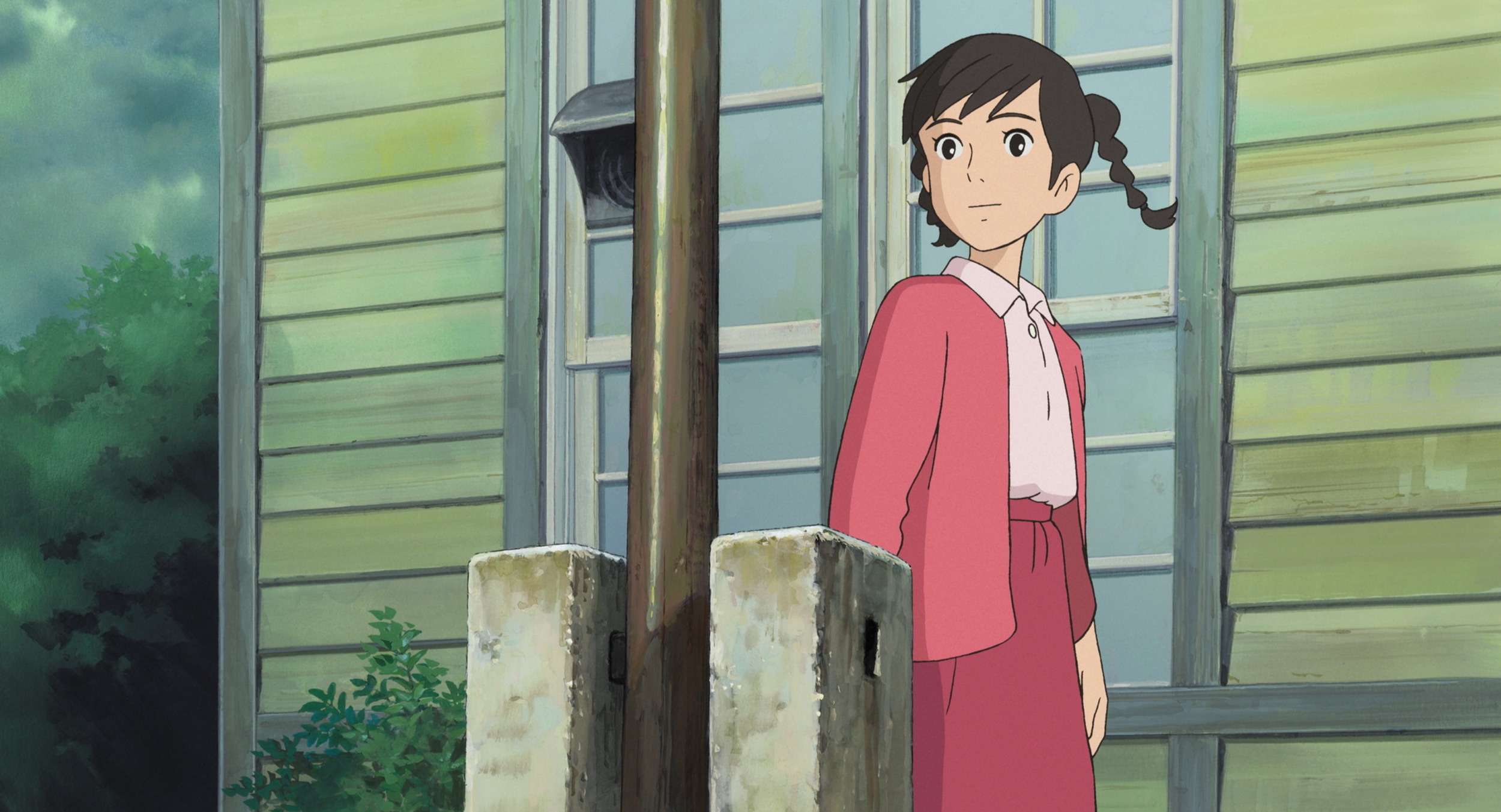

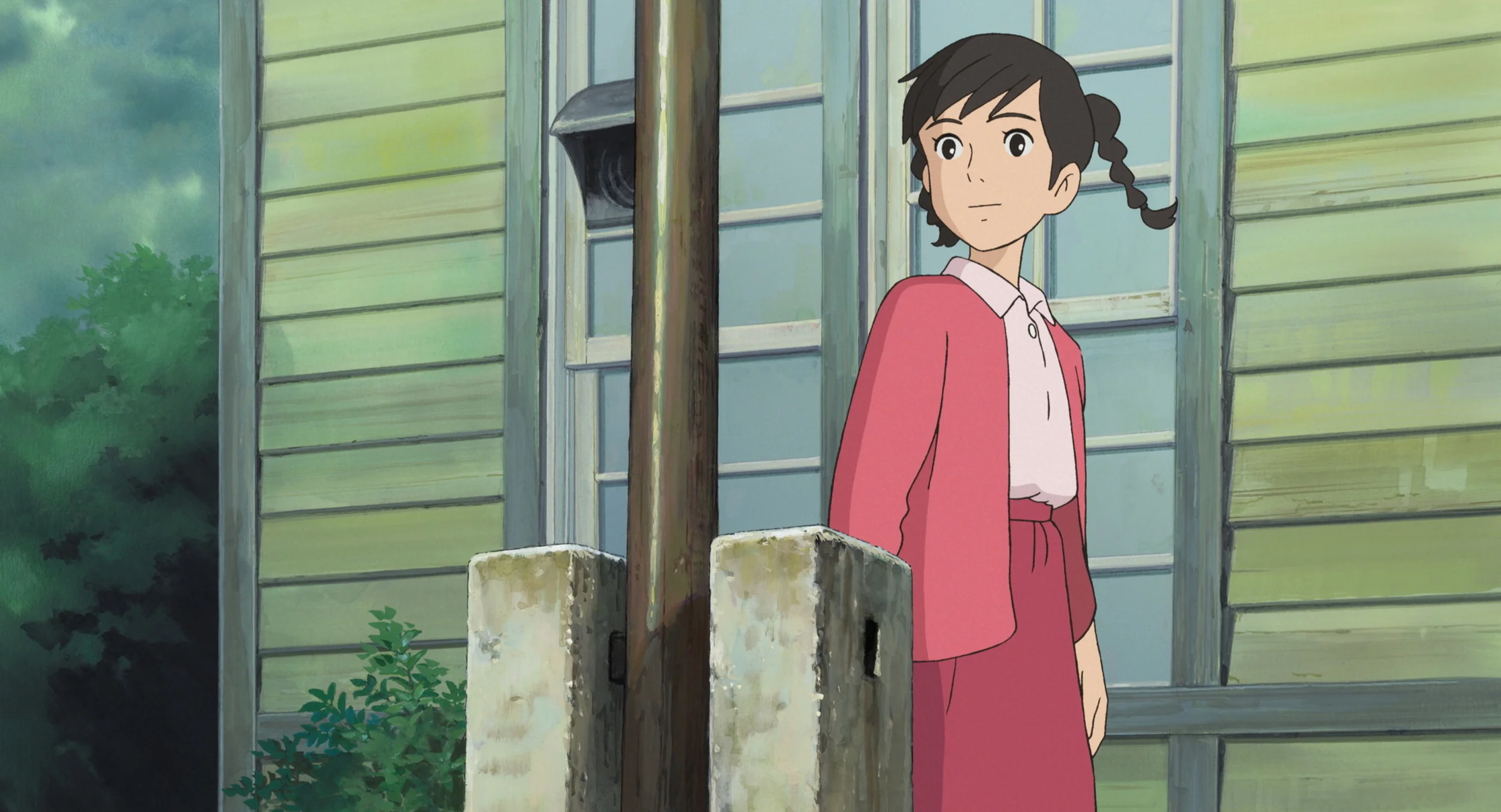

Set in the swirling seaside town of Yokohama in the early 1960′s, the film tells the story of Umi Matsuzaki, a young student who spends her days racing back and forth between the boarding house she runs (while caring for her siblings and her grandmother) and the high school she attends — a model of patience and competence despite being burdened with obligations far beyond her years. Each morning, Umi raises a string of signal flags upon the flagpole in front of the boarding house. “I pray for safe voyages,” they say, and she raises them in memory of her father, a seaman who was lost during the Korean War. (Or does she raise them out of her indefatigable hope for his eventual, impossible return?)

Shun Kazama, a young man moonlighting as editor of her high school paper, notices the flags, and the piece he pens in response draws her gradually closer to him and to the strange building that houses his paper: The Quartier Latin, a dilapidated structure that hosts many of the high school’s more obscure — OK, nerd-infested student organizations. Soon, Umi finds herself battling to balance her growing feelings for Shun and her growing concern over the Administration’s proposed destruction of theQuartier with her already-exhausting obligations at home. And then, things get a whole lot more complicated. (No, I won’t tell. It’d spoil the fun. Trust me.)

The film raises a host of issues: the struggles of post-war Japan, the charms and tensions of young love, the importance and the pitfalls of both filial and familial piety, and the question of just how much reverence and respect one should have for one’s ancestors (and the complexifying role nostalgia can play in that understanding). It is that last point — best captured when one of the film’s protagonists remarks that “You cannot move into the future without first knowing the past” — that is the film’s most explicit “take away” point, and the issue that feels of greatest importance to its creators. But for me, its deepest resonance was not a point it raised directly, but one that surfaced during the unavoidable comparing and contrasting of Poppy Hill with prior, more famous Ghibli releases, and the oft-lost reality underscored by this compare-and-contrast: the value and the wonder found in ordinary life.

Goyo’s famous father (and Ghibli stalwart), the legendary Hayao Miyazaki, once said that “I believe that fantasy in the meaning of imagination is very important. We shouldn’t stick too close to everyday reality but give room to the reality of the heart, of the mind, and of the imagination.” It is a philosophy that permeates his most popular films, and one that I believe helps to explain his gradual, encouraging acceptance as a master filmmaker here in the States.

But in Poppy Hill, his son suggests that giving the mind, imagination, and heart room can look far more “ordinary” than we’re expecting, but that such an “ordinary” reality, properly understood, can be as “wonder-filled” and magic as his father’s fantasy worlds. Unlike Goyo’s first film, an “Earthsea” adaptation that followed most explicitly (and, mostly, unsuccessfully) in his father’s footsteps, this is a more “grounded” work. There are no wizards, no dragons, no soot sprites, no No-Face, no old ladies with incredibly detailed wrinkles. But it’s also a much better work than Tales from Earthsea, and feels far more natural — both in-and-of-itself, and for him as a filmmaker.

To say that it lacks the magical elements of his father’s work is not entirely accurate. There is a magicalness here, surely; but it’s less showy and far subtler. It’s ordinary magic — not better or worse, but much rarer than the sort of magic that has long been Hayao’s currency. Watching it, I suspect that Goyo has discovered that the best way to follow in his father’s footsteps is to recognize and embrace his philosophy — “Give room to the reality of the heart, of the mind, and of the imagination” — but to paint that reality upon an entirely different canvas. It’s not sticking to reality that’s the problem; it’s thinking that reality — the ordinary — is somehow at odds with wonder and adventure and wild places. (Looking for a perfect example of why Ghibli films are so wonderful? The spectacular, Arrietty-esque introduction to the Quartier and its charming, zany residents should do the trick. Fantastic — dare I say “fantastical?” — stuff. Yet somehow, rooted in reality.)

In contrast to his father’s Ghiblis, Goyo’s Poppy Hill doesn’t hum along; it meanders. But that pace — a pace that probably goes a long way towards explaining its limited-release here in the US — is not just appropriate for this story; it’s an essential part of the message. Because this story is not immediately fantastical; it’s only fantastical under the surface. And in that way, Goyo manages to bring his father’s point much closer to home. Ordinary things can seem mundane, but they’re not. They can be just as magical and just as “wonder-filled.” All you have to do is give them room.

The ending is abrupt. But it’ll grow on you.

RELATED: Steven Greydanus says it’s “the summer’s best-kept secret,” and I can’t disagree. I’m sure we’d both love to be proven wrong, though — not because it isn’t wonderful, but because it doesn’t need to stay a secret. That, should you chose to accept it, is your mission.

ALSO RELATED: Fellow Patheosi Nick Olson’s lengthy, highly worthwhile thoughts from over at the Christ and Pop Culture blog.

LASTLY, RELATED: I didn’t want this to turn into a Hayaho Miyazaki Memorial post, so I ignored the elephant in the room. Still, sad times.

![Der_Mohnblumenberg_Szenenbilder_04.72dpi_bba0eca4d_1c89912788[1].png](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5615b175e4b0ecd479d26230/1449352804343-WO5EYAK63RVEWO6P9WNJ/Der_Mohnblumenberg_Szenenbilder_04.72dpi_bba0eca4d_1c89912788%5B1%5D.png)