"To be ignorant of what occurred before you were born is to remain always a child." -- Marcus Tullius Cicero

One of the reasons I have always been drawn to smaller, less mainstream films is their ability to use unusual locales and ethnic environments as the settings for their stories, rather than the highly Americanized environment found in the vast majority of Hollywood fare. Case in point, 2010's The First Grader.

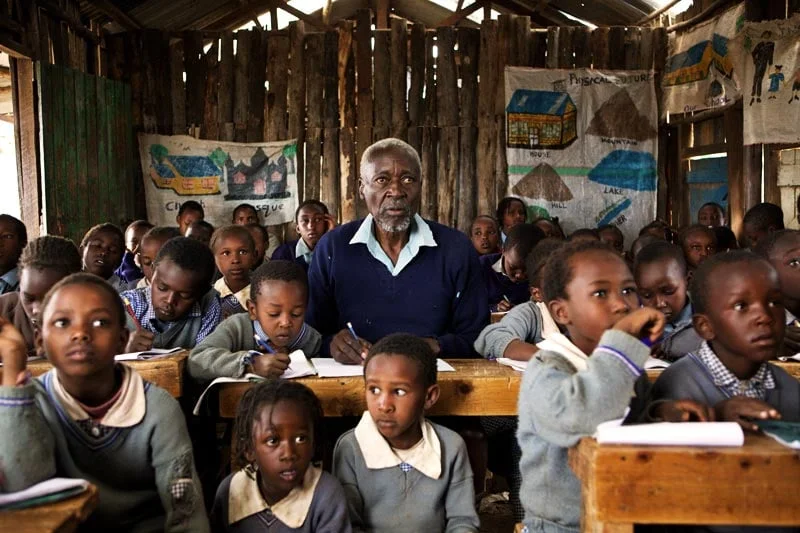

Based on a true story, The First Grader recounts the unusual journey of Kimani N'gan'ga Maruge, an 84-year-old Kikuyu tribesman—and a survivor of the Mau Mau Uprising that signaled the beginning of the end for British Colonialism in Kenya—who takes the government's promise of "free primary education for all" literally, appearing on the doorstep of his local grade school eager to fulfill a lifelong goal: learning to read. Stubbornly refusing to take young headmistress Jane Obinchu's initial refusal as a final answer, the former freedom fighter persists, battles her resistance as fiercely as he battled the English many years before.

Equal parts exasperated and won over, Jane agrees to take him aboard, setting up a most unusual dynamic in the midst of the region's already-overburdened schoolhouse. But the greatest challenge to his success lies not in the schoolroom or in the lowly hovel the aging warrior calls home, but from without—from those who cannot understand his ravenous desire for learning, or those who understand it all too well and seek to thwart (or exploit) it for political, racial, and tribal advantage.

Maruge's tragic past—revealed in disconcerting flashbacks throughout the course of the film—greatly shapes his interactions with his young classmates. (In one of the film's most disturbing scenes, Jane's innocuous request that Maruge sharpen his pencil triggers a horrifying flashback to his days in the camps erected to imprison the Mau Mau, reminding viewers that this stoic, independent elder still carries the scars of his past deep within.) Yet these youngsters embrace their aged companion with the graciousness and kind-hearted indifference so peculiar to children.

The true opponents to his endeavors—the school's suspicious (even furious) parents and the educational board's frustrated bureaucrats—are burdened by his uncomfortable role in a past many Kenyans wish to forget. As the situation escalates, his safety is threatened, his motives are questioned, and the achievement of his missions is called into serious doubt. It seems that everyone around him opposes his efforts—everyone, that is, but the young children who are blessedly free of preconceptions, and the valiant teacher who sees only his desperate desire to learn. In a last-ditch effort to stem the rising tide of tension and violence that threatens to wash away his dreams, Maruge travels to Nairobi to confront the new government's policymakers themselves. But the question remains: will his troubled, troubling past aid him at last, or prove to be the final, unconquerable obstacle to his dreams?

A bit predictable at times—Are there serious doubts as to how Maruge's story will end? And how many Dead Poets Society/The Emperor's Club/Mr. Holland's Opus-style "spectacular but unrecognized by all but their students" teachers can there possibly be?—the film fluctuates between its desire to tell Maruge's extraordinary (indeed Guinness World Record-setting) story and its eagerness to highlight the work of the young woman who makes it possible.

Perhaps more problematically, one begins to wonder if the Loyalists and their British overlords are painted a bit too broadly. There is ample evidence that the reality behind the film is a bit more complex than that which appears onscreen, defying the easy labels used by its storytellers. Maruge/Mau Mau = Good; British Colonialists/their Kenyan Loyalist friends = Bad? That characterization is a convenient one, particularly to those seeking to simultaneously inspire and tell a meaningful story in under two hours. Even the most cursory of journeys through Kenya's multi-faceted history, suggests that the cultural and historical backdrop Maruge's story are not quite as tidy as the film suggests. On that particular front, The First Grader may well be accused of over-simplification.

Setting that important caveat aside, however, the film is both charming and insightful, capturing the extraordinary joie de vivre that is such a refreshing component of many African films while simultaneously underscoring the darker, often violent subtexts that often lie beneath their sunny exteriors. As one of the angry administrators reminds Rose, "the past is always in the present," and the violence, the tribal and racial cleansing, and the ambiguity of its hero's past lurks in the background even of this seemingly innocent story, intruding into Maruge's life despite his best efforts to shield him (and his young companions) from its harsh realities.

The importance of education; the way our drive for freedom impacts everything we do; the power of perseverance—all are explored by the film in timely (if not always profound) ways. But the most intriguing insight offered is a reminder of how important it is to be grateful to our political and cultural forefathers, and how vital it is to recognize both their extraordinary accomplishments and their inevitable mistakes. Few things will guide our futures as well or as clearly as remembering those who came before us, and upon whose shoulders we stand.

Maruge's classmates received an extraordinary blessing of which few of us can boast: the opportunity to live side-by-side with one responsible for the shaping their futures, and the chance to learn of his sacrifice and heroic suffering on their behalf first-hand. And perhaps just as importantly, they were given the chance to hear of his missteps and the things he would have done differently—and from his very own lips.

Even in a country as (relatively) young as America, we are already several generations removed from our founding fathers, and the effects of that removal are obvious. How quickly we forget that our extraordinary blessings are often the result of others' sacrifices, and how easily we ignore the important lessons to be learned from those in whose footsteps we invariably tread. As Americans, we are constantly looking to the future, constantly searching for to "make it bigger, better, and more American." But the future will be far less meaningful (and we will be far, far less worthy of it) if we refuse to recognize the contributions of those who came before.

The words of Rose's angry superior—"The past is always present"—were meant as a threat; his final, unpleasant attempt to remind her that Maruge was "damaged goods," and that she was foolish to expect his desire for learning to overcome the tragic baggage of his (and his nation's) past. But it is not a threat; at least, not exclusively. It is also an important encouragement to those of us inclined to focus too much on our own future. We must make the past always present, because that is a vital part of our ability to understand the time in which we now live. And it is the only way we will see clearly as to what our future can and should be—both for ourselves, and for our children.

(Maruge, now deceased, found the perfect capstone for his amazing story: in May 2009, he was baptized into the Catholic Church—a conversion which he attributes to his newly-won ability to read the Bible.)